NiṣādaHermaphroditarchaṃśa (Mal'ta boy ka parivar)

Some maps to visualize India in antiquity

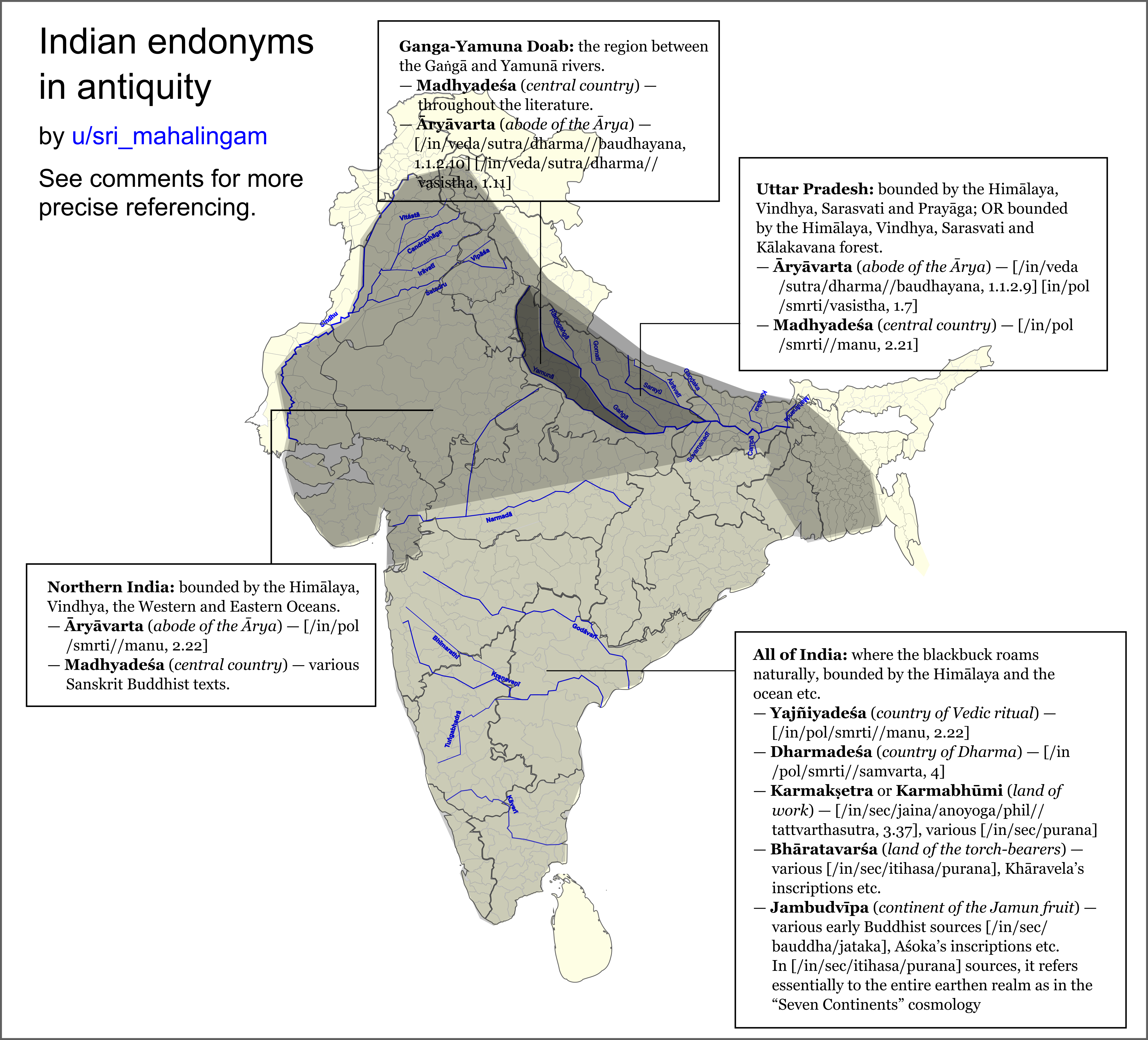

[fig:names_of_india]

A general caveat: A standard feature of ancient Indian culture was that we rarely referred by specific names the water we lived in. Sanskrit was usually just called “language” (“Bhāṣā”) or “correct speech”, India was usually just called “realm” (“Loka”), Hinduism was just called “Dharma” or “the practices of the Āryas”. Many of the references herein simply say things like “wherever the blackbuck roams naturally, the glory of Brahman is present”.

Even when there were actual names for these. This doesn’t mean there wasn’t a sense of identity; they just didn’t care to mention it by name. This practice in still preserved in the speech of old people (”our country”, “our language” etc.), and among Indonesians/Malays who just call their language “Bahasa”.

All of India: where the blackbuck roams naturally, bounded by the Himālaya and the ocean etc.

- Yajñiyadeśa (country of Vedic ritual) — [/in/pol/smrti//manu, 2.22]

- Dharmadeśa (country of Dharma) — [/in/pol/smrti//samvarta, 4]

- Karmakṣetra or Karmabhūmi (land of work) — [/in/sec/jaina/anoyoga/phil//tattvarthasutra, 3.37], various [/in/sec/purana]

- Bhāratavarśa (land of the torch-bearers) — various [/in/sec/itihasa/purana], Khāravela’s inscriptions etc.

- Jambudvīpa (continent of the Jamun fruit) — various early Buddhist sources [/in/sec/bauddha/jataka], Aśoka’s inscriptions etc. In [/in/sec/itihasa/purana] sources, it refers essentially to the entire earthen realm as in the “Seven Continents” cosmology

Northern India: bounded by the Himālaya, Vindhya, the Western and Eastern Oceans.

- Āryāvarta (abode of the Ārya) — [/in/pol/smrti//manu, 2.22]

- Madhyadeśa (central country) — various Sanskrit Buddhist texts.

Uttar Pradesh: bounded by the Himālaya, Vindhya, Prayāga and Vināśana (the spot of Sarasvati’s disappearance); OR bounded by the Himālaya, Vindhya, Kālakavana forest and Vināśana.

- Āryāvarta (abode of the Ārya) — [/in/veda/sutra/dharma//baudhayana, 1.1.2.9] [in/pol/smrti/vasistha, 1.7]

- Madhyadeśa (central country) — [/in/pol/smrti//manu, 2.21]

Ganga-Yamuna Doab: the region between the Gaṅgā and Yamunā rivers.

- Madhyadeśa (central country) — throughout the literature.

- Āryāvarta (abode of the Ārya) — [/in/veda/sutra/dharma//baudhayana, 1.1.2.10] [/in/veda/sutra/dharma//vasistha, 1.11]

Primary sources

[/in/veda/sutra/dharma//baudhayana] Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra, 1.1.2: wisdomlib.org

[/in/pol/smrti//manu] Manusmr̥ti, 2.17—2.24: wisdomlib.org

See comparative notes on wisdomlib.org for references to:

- [/in/veda/sutra/dharma//vasistha] Vasiṣṭha Dharmasūtra

- [/in/pol/smrti//samvarta] Samvarta Smr̥ti

See comparative notes on wisdomlib.org 1(https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-bhagavata-purana/d/doc1127134.html#note-e-190249) 2(https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-brahmanda-purana/d/doc362730.html#note-t-125632) 3(https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-markandeya-purana/d/doc117107.html#note-t-68687) for references to various [/in/sec/purana]

See comparative notes on wisdomlib.org 1(https://www.wisdomlib.org/buddhism/book/maha-prajnaparamita-sastra/d/doc225800.html) 2(https://www.wisdomlib.org/buddhism/book/maha-prajnaparamita-sastra/d/doc225073.html#note-e-53821) and sources therein for references to various Buddhist Sanskrit literature.

[/in/sec/jaina/anoyoga/phil//tattvarthasutra] Tattvārtha-sūtra, 3.37: wisdomlib.org, see also notes on Jinasena’s descriptions on wisdomlib.org.

[fig:india]

[fig:udicya]

North West

https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.4695/page/n77/mode/2up The Agalassoi and Sibae were said to be North from the Malloi (Arrian says Alexander “made inroads” among them to prevent them from confluencing from the Malloi); the ?ibis are associated with U??nara in traditional literature, so I have located them at a region accessible to the Usinara.

The Ambastha are hard to locate from Indian literature, but the Diodorus helps locate them: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/17E*.html#ref83 https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/59648

Some information based on Alexander’s invasion:

Cophen campaign

A people called Aspasioi are found in the Choes (either the Alishang or the Kunar) valley and a people called Assakenoi in the Swat Valley. The Guraeans ruled in the Panjkora valley of the Upper Dir district.

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gYg8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA352

The Kunar Valley starts at Chitral, flows through the Kunar province of Afghanistan, and returns to Pakistan through the Khyber district, until Attock.

The Swat Valley corresponds to the modern-day Swat district. The Assakenoi also controlled the Buner district, and the city of Aornos may have been on Pir Sar in the Shangla district. Pushkalavati, the former seat of Achaemenid power in Gandhara, located on the border of Charsadda and Peshawar, also likely came under their influence in this period.

Narain, A. K. (1965). Alexander the Great: Greece and Rome – 12. pp. 155–165.

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=t5g2EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA24

The Guraeans seemed to have been vassals of the Aspasioi, as the city of Arigaion in Bajaur district is attributed to both of them (sorta).

Dodge, Theodore (1890). Alexander. Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 519.

Abisares was an ally of the Assakenoi, and ruled in Kashmir (including the Pakistan-controlled part shown in the map, and e.g. Rajouri in the India-controlled part).

The part of Ancient Gandhara not attributed to one of these tribes, I have attributed to Taxila.

Hydapses campaign

Porus ruled between the Jhelum and the Chenab rivers.

A certain Glausaes ruled to his North-East.

To his South-East, between the Chenab and Ravi rivers, ruled “the other Porus”, an enemy of Porus, possibly his cousin.

Sakala was not part of this territory, instead belonging to the war-like Cathaeans who originated further East.

Arrian doesn’t name the rulers of the territory between the Ravi and Beas rivers, but Diodorus states it was ruled by numerous divided states including Sophytes, Phegus, the Adrestians etc.

Bosworth, Albert Brian (1993). “From the Hydaspes to the Southern Ocean”. Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press.

Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander, 5.21-22.

Southern Punjab

Alexander subjugated some unnamed Indian states during his voyage down the Jhelum, probably located on its West bank.

Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander, 6.4.

He then traveled down the Chenab. Here too, several unnamed rulers refused to submit to him. Interestingly, Arrian does not describe battles with these rulers, instead merely saying that Alexander prevented them from aiding the Malloi further South (who were preparing for battle against Alexander).

Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander, 6.5.

At the intersection of the Ravi and the Chenab was where the next described battle takes place. The Malloi ruled directly South of this confluence, and I assume that this corresponds to the modern-day Multan division (i.e. as far as the Sutlej-Chenab confluence).

The Malloi allied with the Oxydraci, their historical enemies. Their territory is not known. However, I will note that Arrian does not mention any battles between the Sutlej-Chenab confluence and the Chenab-Indus Confluence, thus I assume this region belonged to the Oxydraci.

Sindh

Musicanus and Oxycanus were likely plains-dwelling rulers in Sindh. Sambus likely had a more mountainous territory in the Western part of Sindh. Patala was a kingdom in the Sindh river delta.

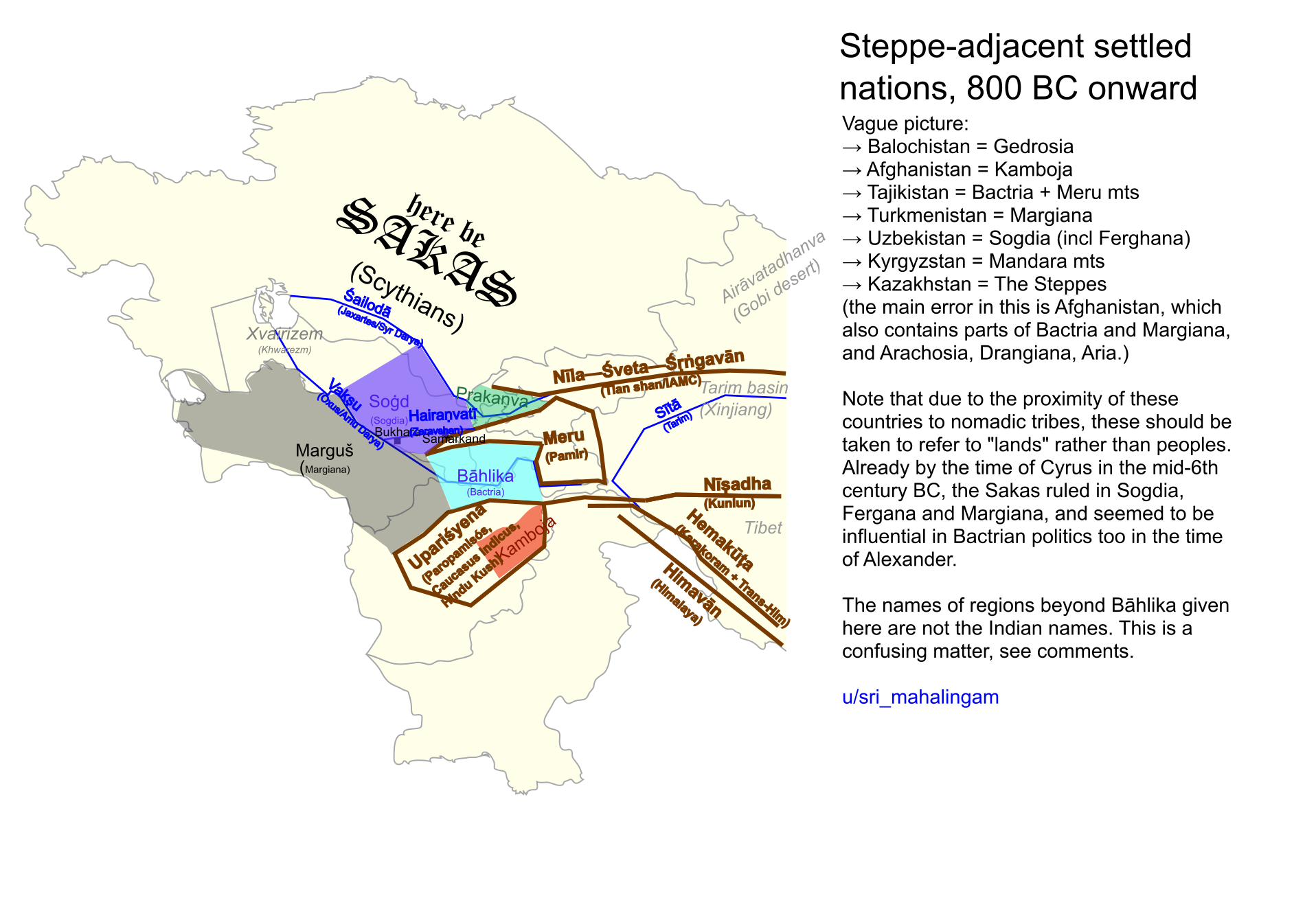

[fig:silk_road]

Vague picture:

- Balochistan = Gedrosia

- Afghanistan = Kamboja

- Tajikistan = Bactria + Meru mts

- Turkmenistan = Margiana

- Uzbekistan = Sogdia (incl Ferghana)

- Kyrgyzstan = Mandara mts

- Kazakhstan = The Steppes

(the main error in this is Afghanistan, which also contains parts of Bactria and Margiana,and Arachosia, Drangiana, Aria; see [fig:afghanistan] for details)

Note that due to the proximity of these countries to nomadic tribes, these should be taken to refer to “lands” rather than peoples. Already by the time of Cyrus in the mid-6th century BC, the Sakas ruled in Sogdia, Fergana and Margiana, and seemed to be influential in Bactrian politics too in the timeof Alexander.The names of regions beyond Bāhlika givenhere are not the Indian names. This is a confusing matter, see below.

Note on Central Asia and foreign realms

There are several different genres of traditional Indian literature on foreign realms, especially on Central Asia, ordered from most grounded-in-reality to most poeticized:

-

Merchants’ tales. Although we know from the history of those regions that Hinduism played equal part in the Indian influences on Central Asia and South-East Asia, its orthodox literature speaks relatively little on trade in realistic terms compared to the Jain texts from the early

centuries AD ([/in/sec/jaina/sveta/a8], [/in/sec/jaina/painna//angavijja], [/in/sec/jaina/anuyoga/epic//vasudevahindi] etc.) and Buddhist texts from the Pali Canon [/in/sec/bauddha/thera/sp5.11], the Jātakas [/in/sec/bauddha/jataka] or other schools [/in/sec/bauddha/lokottara/mahavastu]. With that said Hindu texts like [/in/sec/epic/mahabharata, Sabha Parva] and the [/in/sec/epic/brhatkatha] of Southern origin are also useful. Most of these primary sources are hard to find, I have mostly relied on the secondary source, Moti Chandra’s “Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India”. - The “Uttara- Parama-“ countries. Uttara-kuru, Uttara-madra, Parama-kamboja … these are very difficult to identify. Uttara-kuru is the most prominent of these: in time of [/in/veda/brahmana//aitreya] (earlier than 500 BC) it was apparently a historical place, but by the time of the Purāṇas and Buddhist literature it had taken a mythical role as a paradise of “noble savages” (it was praised as gloriously wealthy, yet nomadic, “suitable only for pleasure, not work” i.e. not a Karmabhumi, sexual frivolousness and absence of marriage)

- The “Mount Meru” cosmology of the Purāṇas. Real mountain ranges and rivers are idealized into a particular geometric model. Various kingdoms are named in these regions, but they are inconsistent and hard to identify because the Purāṇas were composed over a long time period, and because they are given mythical traits (e.g. the Kimpuruṣas having “horse-shaped heads”).

- The Puranic “dvīpas of Bhāratavarṣa” cosmology. Indradvīpa, Kaserumān, Tāmraparṇa, Gabhastimān, Nāgadvīpa, Saumya, Gandharva, Varuṇa. Some have suggested associations like Varuṇa = Borneo, Tāmraparṇa = Sri Lanka, but these seem arbitrary to me, and it’s likely just an idealization of regions in South-East Asia.

- The Puranic “dvīpa/Seven Continents” cosmology. Only Jambudvīpa is real, and refers to the entire physical world, all others are vaguely based on regions of Central Asia (e.g. claiming that the Magi were the Brāhmaṇas of Śākadvīpa).

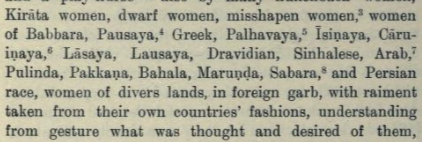

The absence of a standardized name for Sogdia in Indian literature (except for Ferghana, mentioned as Prakaṇva by Pāṇini, see e.g. VS Agarwala) is certainly surprising given the close relationship between India and the region (c.f. the Buddhist monk Kumarajiva), although it is referenced often in Chinese Buddhist literature. This list in [/in/sec/jaina/sveta/a8], of sources of women in a harem in Dvāraka, is illuminating:

source: /in/sec/jaina/sveta/a8(https://archive.org/details/antagadadasaoanu17royauoft/page/28/mode/2up)

Kirata women … women of Babbara, Pausaya, Greek, Pahlavaya, Isinaya, Caruinaya, Lasaya, Lausaya, Dravidian, Sinhalese, Arab, Pulinda, Pakkana, Bahala, Marunda, Sabara, and the Persian race, women of diverse lands, in foreign garb, with raiment taken from their own countries’

fashions, understanding from gesture what was thought and desired from them

Dravidian, Sinhalese, Pulinda, Sabara are Indian nations; Bahala is Bactria of course, Pahlavaya is the Parthians, Babbara is probably Somalia, and Pakkana might be Ferghana. Pausaya, Isinaya, Caruinaya, Lasaya, Lausaya, Marunda are hard to identify, but Moti Chandra suggests they are places in the trans-Oxus country i.e. Sogdia, Margiana etc:

The list of the foreign female slaves in the Antagaaadasao is also interesting as it informs us that they came from the trans-Oxus country, Ferghana, Sri Lanka, Arabia, Balkh, Iran etc., and employed in the harems for service.

Identifications of rivers in Central Asia

The Purāṇas mention that four rivers originate out of the Meru mountain, but they are oddly identified as the Sīta, Gaṅga, Indus, Oxus. The myth is reflected in Buddhist literature which specifies that these rivers proceed from the North, East, South and West of the “Anavatapta lake” respectively (see wisdomlib.org).

It seems likely that Sita was used to refer to multiple rivers, including the Syr Darya and the Tarim, see note on wisdomlib.org. E.g. the Brahmanda Purana suggests the river flows Westward, which would contradict being the Tarim river, see wisdomlib.org -(https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-brahmanda-purana/d/doc362834.html) -(https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-brahmanda-purana/d/doc362725.html#note-t-125584)

But the Mahabharata suggests that the Sailoda flows between the Meru and Mandara ranges, and Mandara seems to be an alternate nae for the Tian-shan, making that the Syr Daria. The Mandara has also instead been identified as the Alay range, see wisdomlib.org. But I think this is unlikely because Mandara is said to be Eastward of Meru (Alay is the Westward projection of the Pamirs), and there is also no river valley of significance “between the Pamir and Alay” (Bactria lies between Pamir/Alay and the Hindu Kush).

Another brief wisdomlib.org summary. I’m not bothering to reference these links systematically, because for anyone who really cares about this subject beyond making obvious the simple fact that the Purāṇas contain a geography of Central Asia, the comprehensive source on this matter is:

M. Ali (1966), Geography of the Puranas. 286 pages. Full text from archive.org.

Further reading

M. Ali (1966), Geography of the Puranas. 286 pages. Full text from archive.org.

Canonical sources

Moti Chandra (1977), Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India. 294 pages. Full texts from archive.org, indianculture.gov.in.

VS Agarwala (1953), India as known to Pāṇini. 594 pages. Full text from archive.org.

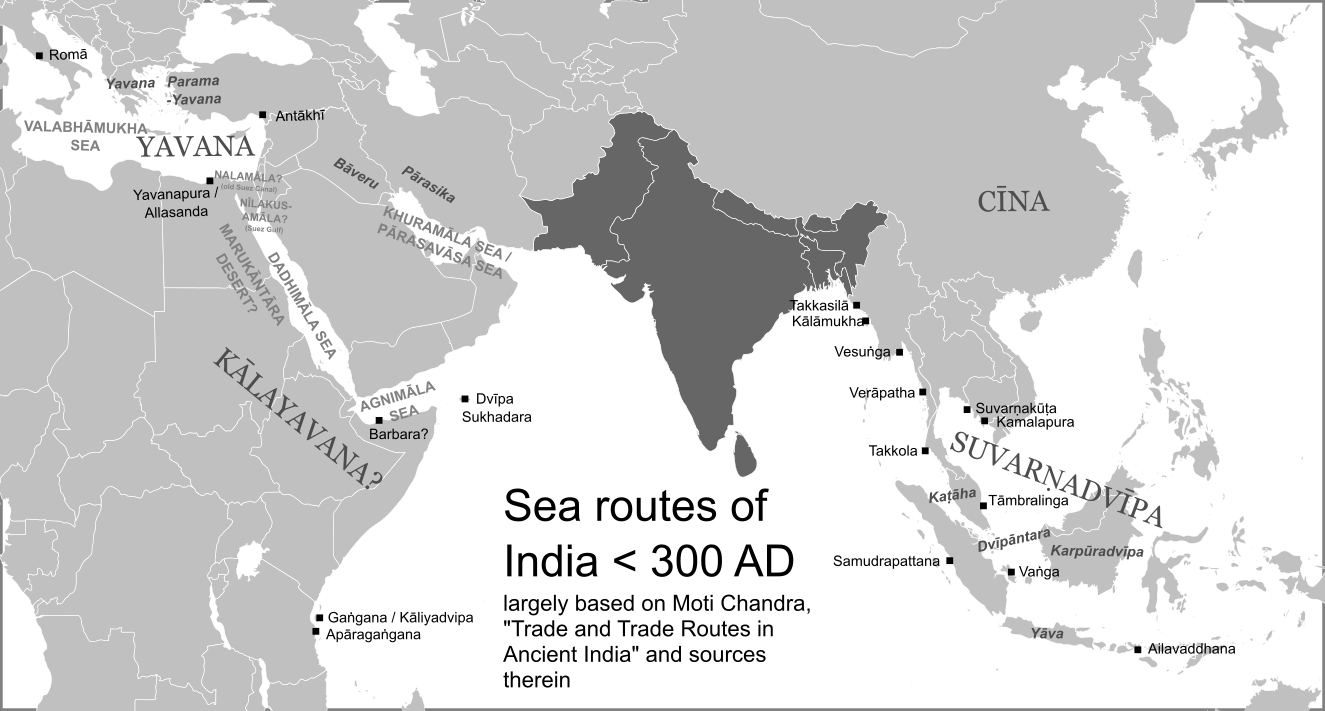

[fig:maritime_trade]

Canonical sources:

Moti Chandra (1977), Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India. 294 pages. Full texts from archive.org, indianculture.gov.in.

[fig:afghanistan]

Kamboja is only attested in Indian literature (to the Iranians it was just the Uparisaina mountains, part of Gandāra), apart from the name of the Achaemenid emperor Kambūjiya (see also Kūruš, that is Cyrus).

Alexander’s route: Aria → Drangiana → Arachosia → Uparisaina → Bactria → Margiana → Sogdia → Punjab → Sindh → Gedrosia

All four Alexandrias here existed before the Greeks; Ai-Khanoum was built by the Greeks.

The Haraxvatī and and Harī rivers are cognate to the Sarasvatī and Sarayū. The provincial names Arachosia and Aria are Hellenizations of the same.

[fig:south_east_asia]

Earliest recorded Indian rulers in Southeast Asia:

- Kaundinya, Cambodia, 1st cen

- Śrī Māra, S. Vietnam, 1st/2nd cen

- Deva-varman, Java, 132 AD

- Langkasuka, Malaya, ~100 AD

For SEA to be so fully Indianized in the 2nd cen, trade and influence must have began much earlier.

Founding legends of Southeast Asian countries:

- Funan, Cambodia by Kaundinya

- Langkasuka, Malaya by a Mauryan prince

- Java, by a Kuru prince through Gujarat

- Sankissa, Upper Burma by Abhirāja of Kapilavastu

- Thaton, Lower Burma, by Mauryan-era Andhra explorers

Oc-eo in Vietnam was an Indian trading colony from ~200 BC, and later part of Kaundinya’s kingdom in the 1st cen. It was an important stopping point on the journey from India to China, and notably hosted the Romans in their first embassy to China (120, 166 AD).

Indian-Chinese maritime trade began in the 2nd cen BC. As Chinese vessels were too low-quality at the time to pass through even Vietnam, Indian vessels made basically the entire journey, thus providing the impetus for the Indian colonization of SEA.

Indianization in SEA suffered a set back in the 3rd and 4th centuries, and was re-invigorated in Funan by Kaundinya II c. 410, and by extensive Pallava involvement. Funan would fall in the 7th century, giving rise to the era of empires like Śrīvijaya, Śailēndra, Yaśōdharapura (Angkor).

Canonical sources:

RC Majumdar (1979), Ancient Indian Colonization In South East Asia. 109 pages. Full text from archive.org.

Moti Chandra (1977), Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India. 294 pages. Full texts from archive.org, indianculture.gov.in.

[fig:cities]

Sources:

- Maurya-era Pāṭaliputra: Megasthenes

- Taxila: Life of Apollonius

- 7th century cities: Xuanzang

- Gupta-era cities: Xuanzang’s descriptions of “old city” ruins are taken to be Gupta-era

- pre-Maurya cities: excavations

- Rome: Aurelian wall, Servian wall

- Carthage: Roman city plan https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_carthage_romaine.jpg

Others are known from excavations. Xuanzang gives the city wall perimeters, area estimates herein assume a square size city (this is OK because Indian city walls only enclosed the city and nothing else). Unfortunately have almost no records of city sizes during the entire economic boom period between 300 BC and 500 AD.

One may note the destruction of Taxila by the Huns, and the emergence of Frontier regions over the classic Gangetic plain post-Gupta, this I would attribute less to Huns and more to soft and anti-Kautilyan attitudes that had emerged post-Gupta (strong men, good times, weak men etc).

Not included: Chinese cities, because their size would dwarf everything else here. This was mostly due to Chinese flair for grandeur: Chang’an in the 2nd century BC had much fewer people than Pāṭaliputra or Rome, but was 36 km2 in area; in the 6th century it was an enormous 84 km2.

[fig:writing_systems_modern]

[fig:meme_map]