NiṣādaHermaphroditarchaṃśa (Mal'ta boy ka parivar)

A political history of premodern India (1200 BC - 1756)

A brief walkthrough of Indian political history, focusing on the actually important things rather than just the stuff there are more tertiary sources on/that historians care more about.

Table of Contents

- Prologue: the thousand-year recession

- Early Iron Age (1200 BC – 750 BC)

- Middle Iron Age (750 BC – 493 BC)

- Late Iron Age (492 BC – 323 BC)

- Classical Age: First Golden Age (322 BC – 269 BC)

- Classical Age: Civil War period (268 BC – 181 BC)

- Classical Age: Invasions period (180 BC – 249 AD)

- Classical Age: Second Golden Age (250 – 543)

- Classical Age: Intermediary period (544 – 749)

- Classical Age: Third Golden Age (750 – 1194)

- Dark Ages: Muslim period (1195 – 1669)

- Dark Ages: Reconquest period (1670 – 1756)

Prologue: the thousand-year recession

The political system of Bronze Age India was probably a plutocracy.

In its peak, the Indus Valley civilization was the source of various technological innovations particularly in the fields of agriculture, water management, infrastructure and measurement. As the Indus Valley script remains undeciphered and very little of its writing remains, it is harder to comment on its academic achievements, most of these are first known from Mesopotamia (Egypt is a somewhat overrated Bronze Age civilization – it showed very little urbanization and was also a late adopter of the wheel; it just has an impressive archaeological record because of its palace economy).

In 1900 BC, a global depression struck. Indian cities crumbled; Near Eastern cities turned into stagnant palace economies; almost no inventions date to this period.

And then in 1200 BC, civilization collapsed.

It was the most mysterious event: Cities throughout the world burned and perished, literacy vanished, disease and local violence became widespread – civilization, from Greece to Gujarat, just collapsed.

Many historians posit pseudo-explanations for the Late Bronze Age collapse, like climate change, or “General Systems Collapse”, but none of these “explanations” are really good as scientific theories. Folks of the time were as confused by the event as we are – a letter from the Syrian king Ammurapi to the king of Cyprus reads:

My father, behold, the enemy’s ships came (here); my cities(?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots(?) are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka?… Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.

To which the governor of Cyprus responded:

Concerning those enemies: (it was) the people from your country (and) your own ships (who) did this! And (it was) the people from your country (who) committed these transgression(s)…I am writing to inform you and protect you. Be aware!

Following the collapse, the various peoples of the old Bronze Age world constructed several theories to explain the events of the decades prior. The Greeks blamed themselves for it and created the fabulous story of the Trojan war; well, stories of wars being fought over women are like photographs of the Big Foot, but the destruction of Troy was a historical event and seemed to have made a particular impression on the Greeks.

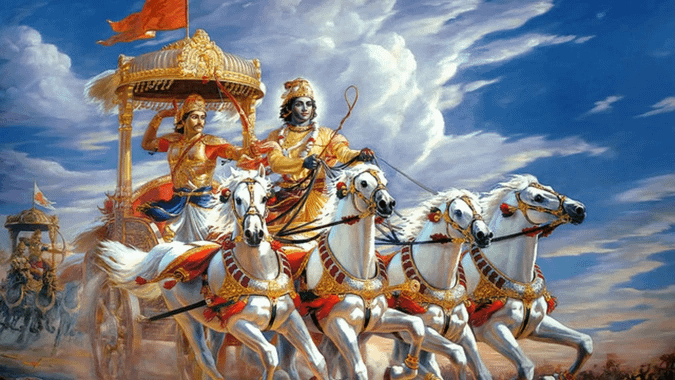

In India, while Vedic literature only mentions the drying of the Sarasvati river, bardic legend postulated a conspiracy that eventually formed the basis of the Mahabharata: briefly, Krishna, the ruler of Dwaraka, creates an elaborate plot to manipulate the states of the world into a costly war to wipe out the prevailing political establishment and rid the world of the cultural degradation of the Late Bronze Age so that civilization can start anew.

The Mahabharata is a brilliant piece of literature: it has intelligent and ambitious characters (Krishna, Shakuni), passionate characters (Arjuna, Draupadi, Abhimanyu, Drupada, Shikhandi), and NPCs (Yudhishtira, the entire Kuru state), each with their own goals and schemes, only to ultimately find these schemes as tools for Krishna’s grand agenda; its characters plot and strategize, rather than just find their luck at the mercy of the plot; and the text was eventually expanded to cover various philosophical themes (most famously the Bhagavad Gita) as well as various regional tales of India. The postulation of a conspiracy, however, is likely to be a simplification of emergent social phenomena, and specific characters are likely to be personifications of such phenomena, an example of the Great Man Theory.

For years to come, the Late Bronze Age collapse inspired the pessimistic myth of the Four Ages in both India and Greece, as people extrapolated the decline in prosperity and order to a continuous decline in human morality from the beginning of time.

And then around 1200 BC, man struck iron.

Early Iron Age (1200 BC – 750 BC)

Iron smelting was simultaneously invented in India and by the Hittites, and spread so rapidly across the world that the precise location of its invention cannot be pinned down, and by 800 BC it had spread across almost the entirety of the old world. While iron, mainly meteoritic iron had been used in small quantities in some sites in India and Egypt for millennia, the large scale production of iron for tools and weapons brought vast social and economic changes throughout the world. Bellary (let’s call it Kishkinda), an early site in the Deccan, was one of the earliest centers of iron mining, and Southern India remained the world’s premier metallurgical center for millennia to come.

Iron was cheaper and far more abundant than bronze, making it accessible to the folk outside the nobility. Large quantities of forest could be cleared for the first time, allowing for large-scale settlement and urbanization of regions outside of the “Desert Stretch”. As metal was no longer monopolized by the state, the importance of private guilds and merchants increased relative to governments and nobility, leading to the development of cities far larger than ever seen before.

This radical change in the way of thought about social organization occurred in the Kuru kingdom (around modern-day Delhi) c. 1000 BC. While the traditional Aryan political system had revolved around the nobility, at some point some people in the Kuru kingdom decided that they in fact valued knowledge and learning more than nobility and government, and they began ambitious project to compile all the known knowledge of the time into a corpus of literature known as the Vedas (lit. knowledge).

This culture, the Vedic culture, which came to expand Eastward, to win and to dominate Indian politics and thought for centuries forth, was the ideological manifestation of the brave new world that was the iron age.

(After the Salva invasion of Kuru, Panchala under Kesin Dalbhya, and Surasena under various rulers including Kuru migrants would become the centres of Vedic civilization.)

Middle Iron Age (750 BC – 493 BC)

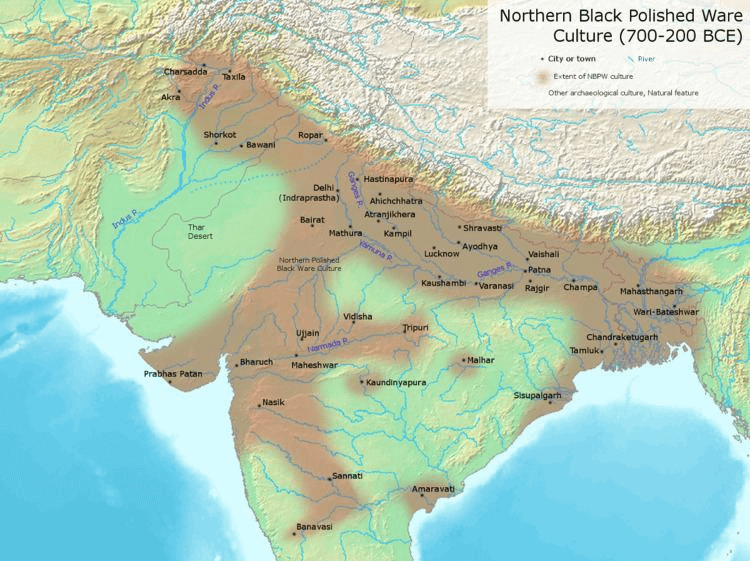

A host of advancements, known as the Second Urbanization, began around the 8th century BC, centered around the kingdom of Ayodhya. Large walled cities appeared across the Gangetic plain, facilitating an expansion of the Indian economy. Various financial innovations came into existence, e.g. loan deeds, and the world’s earliest coins probably having been minted in Ayodhya. The sciences came into existence: mathematics, medicine, economics, linguistics; supported by universities such as Taxila. The Great Highways – the Uttarapatha (Northern Road) and Dakshinapatha (Southern Road) – were built, expanding trade and commerce. Civilization reached the Tamil country, and the tribes of the Dandaka forest were subdued, making it accessible for medicine, hunting and timberland. Yajnavalkya, the father of philosophy, wrote the two oldest known philosophical texts: the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and the Shatapatha Brahmana, the latter of which is also one of the earliest texts (alongside the Apastambha and Baudhayana sutras) to mention the Pythagoras theorem, thus starting mathematics as we know it. The Upanishads suggest a culture of free debate and skeptical inquiry, and spawned the various Indian philosophical schools.

Ancient India as we know it was born.

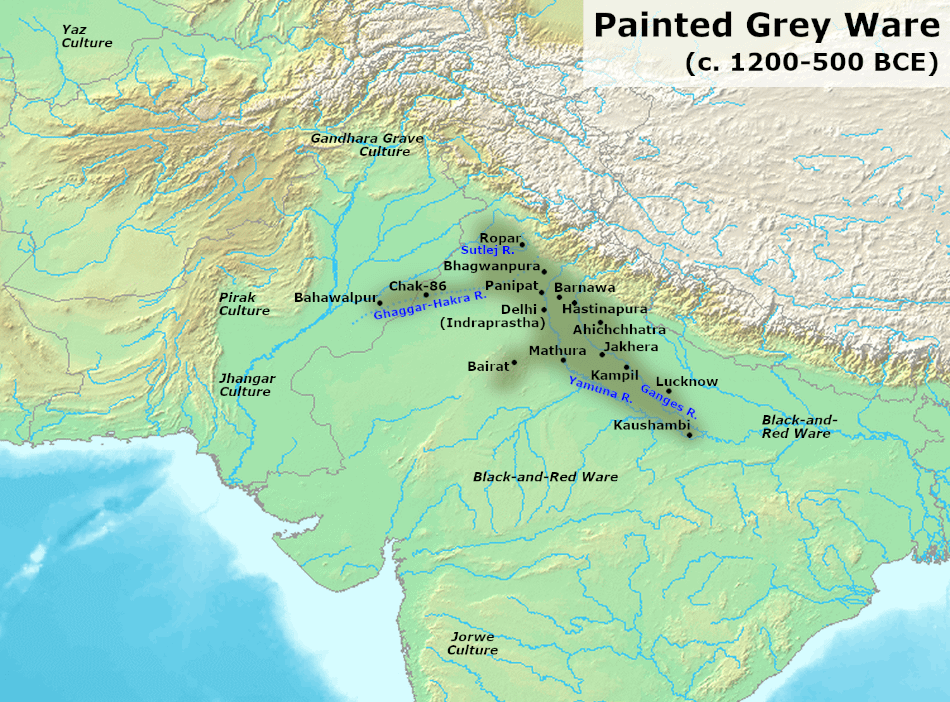

Large cities of Iron Age India, per archaeological excavations. The Mahajanapada kingdoms, that are of central focus in Buddhist texts, are a bit biased towards the cities of the region east of Varanasi.

The epic narrative Ramayana attributes the advancements of this period to the Ayodhyan prince Rama – e.g. the university of Taxila is described as having been established under Rama’s rule and administered by his brother and provincial governor of Gandhara, Bharata. Vedic literature, on the other hand, attributes each of these achievements to different men:

- The enlightenment and philosophical ideas that built this glorious civilization is attributed to philosophers like Yajnavalkya, a native of Ayodhya who flourished in the court of King Janaka of Mithila.

- The Kingdom of Ayodhya (Kosala) became particularly prosperous and influential, creating the culture known today to historians as “Greater Kosala”.

- The taming of the Dandaka forest is attributed to a state known as Dakshina Kosala (South Kosala).

- The transmission of ideas to the South is attributed to Sage Agastya; this is also corroborated by Tamil texts. While Northern texts discuss Agastya’s introduction of Sanskrit and the Vedas to the South, Tamil texts describe his introduction various agricultural advancements and urbanization.

- The University of Taxila is attributed to the sage Uddhalaka Aruni, who migrated Westward from Ayodhya.

Republics also became commonplace, alongside monarchies, during the Middle Iron Age – apart from some sparse and mountainous states (e.g. Buddha’s Shakya kingdom), the states of Kuru, Panchala, Mathura, Kushinagara, Vaishali and Kamboja followed republic or king consul constitutions at various points, with Vaishali probably a direct democracy. Some people also like pointing out that among the scholars who challenged Yajnavalkya in debate were two women, Gargi Vachaknavi and Maitreyi, the latter of whom would later become his wife.

Late Iron Age (492 BC – 323 BC)

The Late Iron Age begins with the coronation of Ajatashatru of Magadha. In the 5th century BC, all the states of Northern India bar Magadha were dominated by the prosperous and urban Vedic culture, that among other features placed Brahmins at the top of the caste system. The relative backwater of Magadha, which retained the more traditional kshatriya-centric pre-Vedic system, was the arch-enemy of Vedic civilization in the latter’s literature, and its expansion tilted the political balance between the three castes.

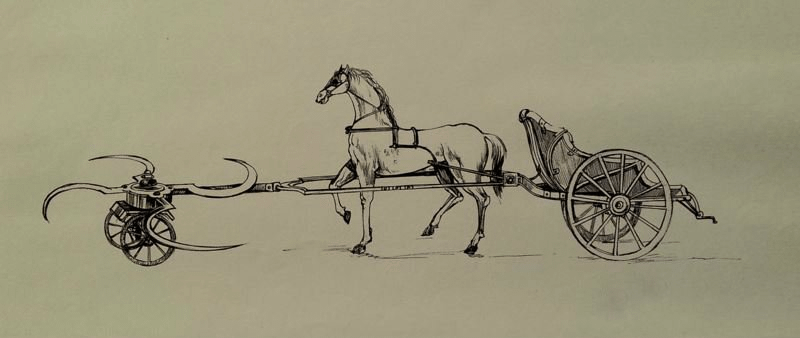

Ajatashatru was a brilliant inventor, who created several military contraptions including the catapult and the famous scythed chariot. He then used these devices to go on a murderous rampage, conquering the states of Champa, Vaishali, Varanasi, Malla and even Ayodhya. The city of Mathura resisted Magadhan conquest for 150 years, a feat that is attributed to the celebrated Vrishni heroes – Samkarshana, Vāsudeva, Pradyumna and Aniruddha. The cult of Vāsudeva became particularly influential, and would eventually form the basis of the legend of Krishna-worship.

Ajatashatru’s expansion brought him into tussle with another rival empire-builder, Pradyota of Ujjain, leading to the Avanti-Magadhan wars. The Magadhan (Pataliputra) Empire and the Ujjain Empire would form two of India’s three longest-lasting empires alongside the later Deccan Empire, lasting under various dynasties for a period of nearly 2000 years, the Imperial Age of India.

The Late Iron Age also saw the beginning of West and Central Asian raids in North-Western India (Pakistan), with the Persian invasion of the Indus Valley. Despite the North-Western region (except Gandhara) being a relative backwater in India, these regions formed some of the wealthiest provinces of the Persian empire: Gandhara was the richest of all Persian satrapies, and Sindh contributed a third of the empire’s total tribute revenue. While all other satraps paid their tributes in silver, the Indian states paid theirs in gold.

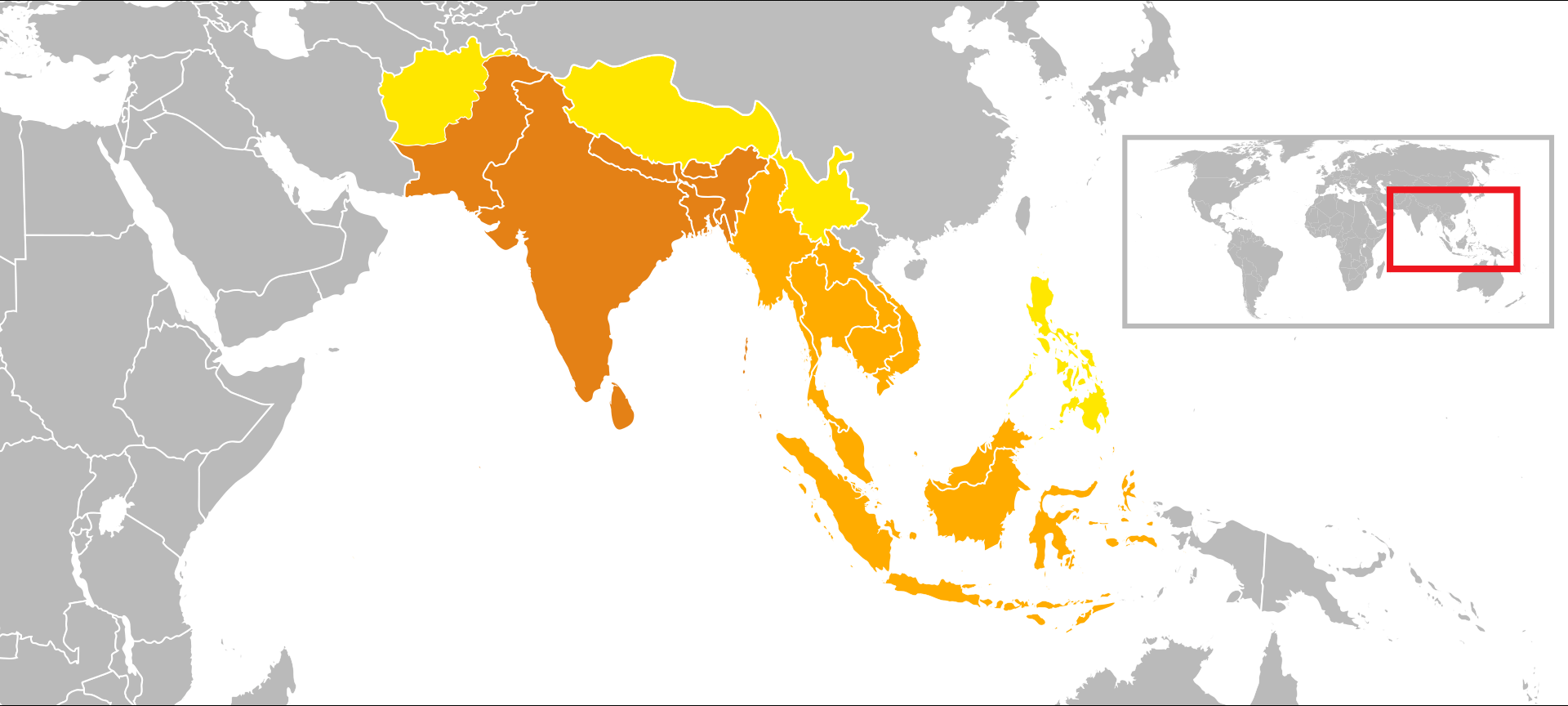

Meanwhile the kingdom of Anga in modern-day Bengal/eastern Bihar transformed into a powerful thalassocracy whose merchants traded with distant lands in South East Asia, beginning the Indianization process in South-East Asia. The founding legends of many South-East Asian states include an origin at Anga: Funan (Cambodia) was supposedly established by the Brahmin merchant Kaundinya who married the local Naga princess Soma after defeating her pirate army; its capital Champa is named after Anga’s capital of the same name. A similar story comes from Sri Lanka, but with a prince instead of a merchant and a Yakshini instead of a Naga.

Classical Age: First Golden Age (322 BC – 269 BC)

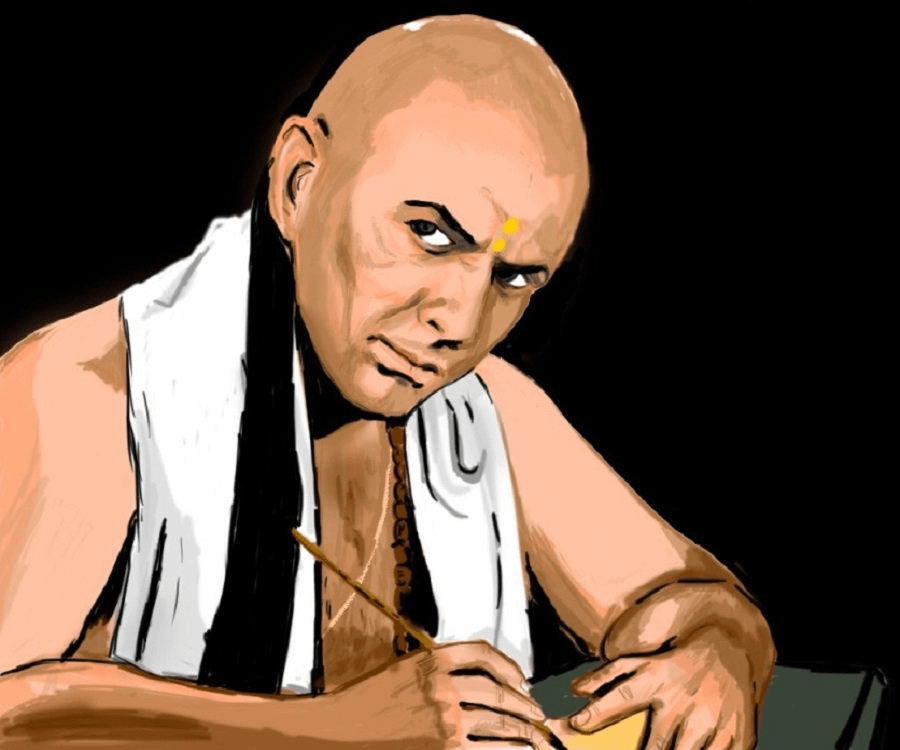

The history of Classical India begins with the polymath Chanakya: father of economics, founder and first Prime Minister of the pan-Indian Maurya Dynasty, father of cryptography, and a brilliant military tactician.

Chanakya was probably a Deccanite Brahmin (based on Jain sources and modern analyses of the context of the Arthashastra) – it is generally agreed that he studied in Taxila, and was strongly influenced by both Carvaka and Hindu philosophy. His magnum opus, the Arthashastra (“Science of Wealth”), begins with salutations to Brihaspati (the legendary founder of the Carvaka philosophy); it declares economics as the fundamental social science, wealth as an encapsulation of human goals, and its maximization the goal of government policy. However, he mentions his differences with the Carvakas (the “school of Brihaspati”) on areas where he displays a more conservative Hindu outlook, e.g. accepting the fundamental role of the physical sciences (“Anvikshaki”) as well as of morality.

On economic policy, the Arthashastra prescribes low taxes, market freedom and public-private partnerships for infrastructural developments, as well as state measures to discourage ascetism and increase productivity and industriousness. On statecraft it describes an efficiently organized state, and extensively discusses foreign policy covering areas including espionage, diplomacy, war strategy and logistics, and military technology. The political position of the text is significantly to the right of ancient Western philosophies, e.g. usury is considered an acceptable source of income.

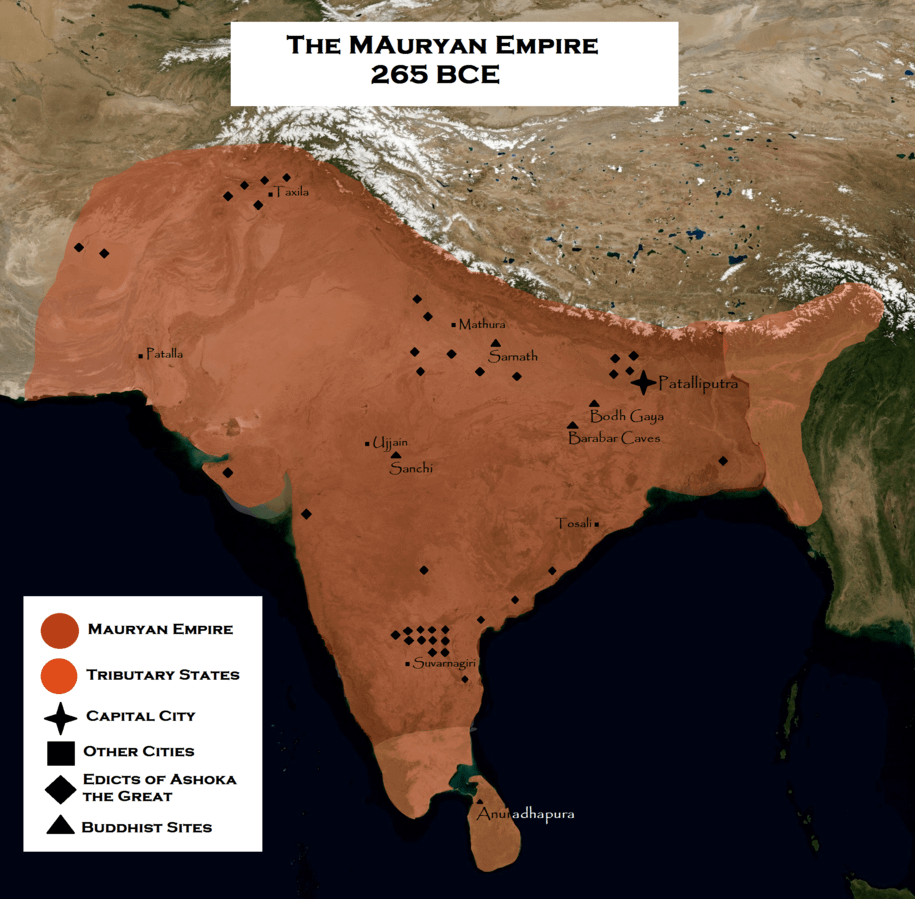

Chanakya’s primary contribution to the political landscape was his plot to instate his protege Chandragupta on the throne of Magadha, thus Sanskritizing the Magadhan empire. Under his ministerial leadership, the empire went on to unite the entirety of the Indian sub-continent*, covering at its peak a third of the world’s population and half the global economy.

The precise sequence of events that lead to the establishment of the Maurya Dynasty in Magadha isn’t clear, but the following facts seem likely:

- Chanakya started with very little capital, and grew it rapidly to raise an army.

- Chandragupta was originally of non-royal birth, and Chanakya declared him as a kshatriya on basis of his merits.

- The dynasty was associated with the peacock, suggesting that Chandragupta’s base might have been in Mathura.

- An initial direct military attack on Pataliputra had failed.

- Much of Chanakya’s success involved complicated manipulations of various governments including Central Asians, Himalayans, Persians, Greeks and Magadha rather than a brute force attack.

- Chandragupta’s army when invading Magadha included Greek and other mercenaries.

The early Mauryan period (under the rule of emperors Chandragupta and Bindusara) was a golden age in Indian history, with massive economic and infrastructural expansion and the development of various new financial innovations such as private corporations, cheques and the double-entry bookkeeping system. Panini’s formalization of Classical Sanskrit grammar dates to this period, as does the mathematician Pingala who set the groundwork for later classical Indian mathematical traditions.

The later popularity of Vaishnavism was partly rooted in the foundation of the Maurya dynasty, as the dynasty was the culmination of Mathura’s resistance against Magadhan rule. The Bhagavad Gita, a synthesis of Upanishadic philosophy, the legend of Vāsudeva, and the earlier Mahabharata legend, was probably written during this period.

The Maurya-Seleucid treaty facilitated an expansion in trade and migration between India and Greece and allowed for the transmission of ideas and knowledge. For example, Indian merchants, who dominated East-West trade, introduced various financial innovations to the societies they frequented, and Indian tradition credits the Greeks as the source of classical Indian astronomy.

- the Tamil country is not usually shown as having been directly under imperial rule, but Tamil Sangam literature shows heavy Mauryan influence in the Pandya government.

Classical Age: Civil War period (268 BC – 181 BC)

The late period of the Mauryan dynasty, starting with the coronation of Ashoka the Great, which is short for “Ashoka the Greatest Argument in Favor of Abortion”, is the only period in pre-medieval India with documented evidence of systematic ideological persecution and political intolerance. Among his many crowning achievements, Ashoka:

- Established a national moral police and a Ministry of Morality

- Allocated a large fraction of state resources to political propaganda and Buddhist proselytism

- Criminalized blasphemy and heresy, brutally persecuting rival philosophies

- Built a torture chamber underneath his palace

- Punished an uprising in Kalinga by mass-murdering his own civilians

- Installed an imperial harem of women, then burned them to death when he heard them call him short and ugly

- Exterminated the Ajivika philosophers in a systematic genocide

- Another genocide against the Jains which was later called off because too many non-Jains died

- Another genocide against “fake Buddhists” (people who pretended to be Buddhist to receive government funds)

- Eventually bankrupted the empire with his fiscally irresponsible programs

The civil unrest and tensions eventually culminated in the Great Civil War of 230 BC, resulting in a tripartite split of the empire. Although the Brahmins were not themselves persecuted by Ashoka, they pretty much led the revolution against what had become of the Mauryan dynasty. The South seceded, lead by Simuka, who founded the Deccan Empire. Back at Pataliputra, an anti-Buddhist faction formed (supported most famously by Queen Tishyaraksha and her son Dasharatha), and various revolts and uprisings throughout the empire resulted in a split of the remaining Northern empire between Ashoka’s heirs Dasharatha and Samprati, who ruled from Magadha and Ujjain respectively.

A particular consequence of this division – which would be exacerbated in the following centuries due to the Buddhist patronage of Central Asian invaders – was the “Big Switch” in the geography of the Indian ideological divide. Magadha, which had once been the enemy of Vedic civilization, was now a Vedic dominion, while the North-Western cities of Mathura, Ujjain and Taxila came under Buddhist influence.

The Great Civil War – and the Mauryan dynasty with it – came to a whimpering end in 180 BC with the assassination of the emperor Brihadratha Maurya by his general Pushyamitra Shunga during a military parade.

Classical Age: Invasions period (180 BC – 249 AD)

The end of the Late Maurya dynasty greatly reduced Buddhist and other non-Hindu political power in India: the Shunga dynasty and the Deccan Empire’s Satavahana dynasty were both not only non-Buddhist, but were ruled directly by Brahmin emperors. In an attempt to reclaim political power, the Buddhists supported various central Asian invaders in exchange for political patronage; it is not clear precisely how they did so, perhaps it was the Buddhists who had enjoyed positions of political power in the Magadhan empire from Ashoka’s time on who were in a position to commit treason.

The first of these invaders were the Greco-Bactrians c. 180 BC, who plundered Mathura, Ayodhya and even Pataliputra before being repelled by the heroic Kalingan commander Kharavela who came to aid the empire that had once massacred his people. They continued to have a presence as far as Mathura for about 20 years where they harassed the local Mitra rulers before eventually being defeated by them.

Next came the Scythians c. 80 BC, who plundered the western country-side and briefly even occupied Mathura c. 60 BC.

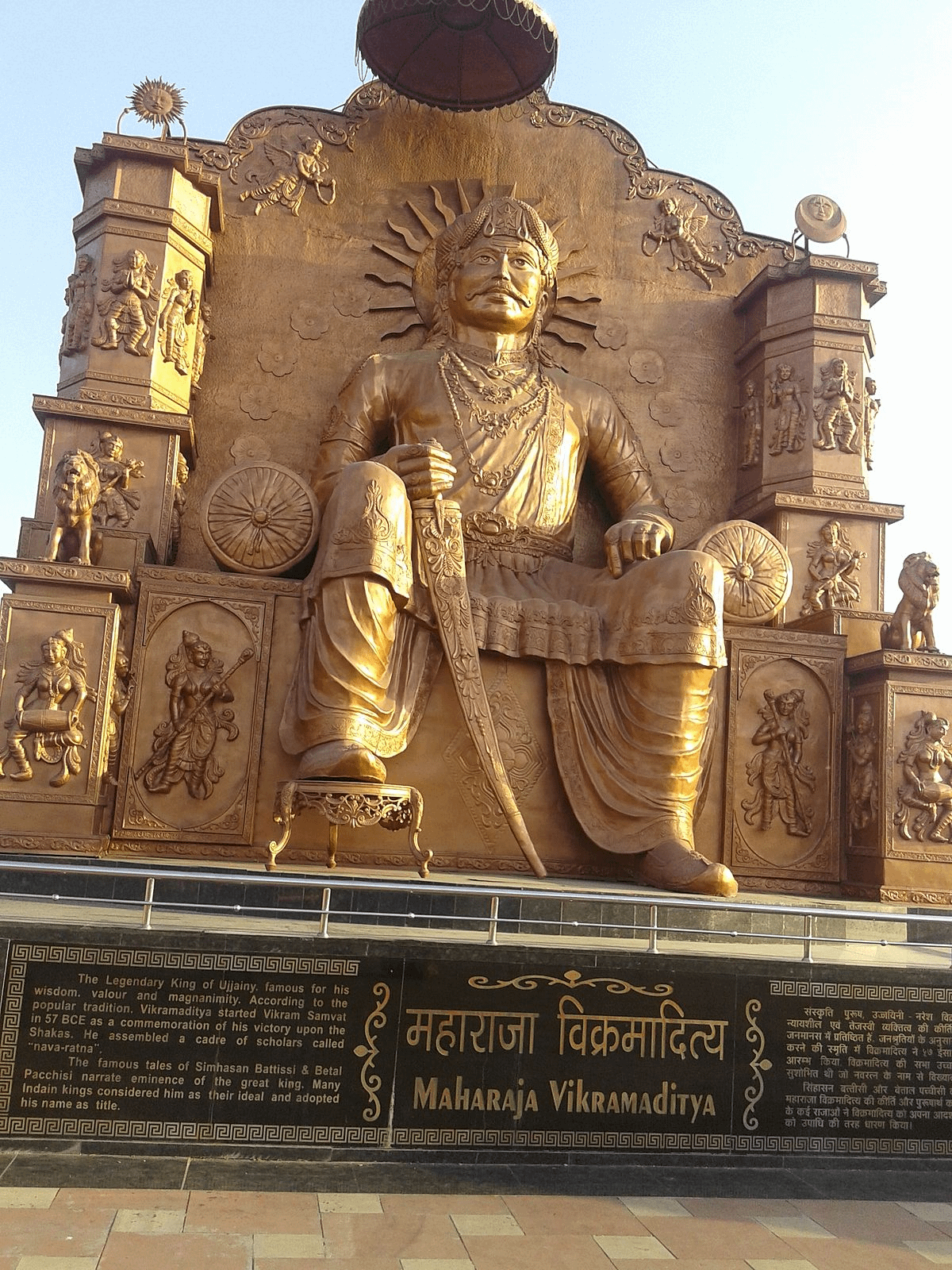

The key political figure from the period is Vikramaditya, who re-established the ancient Ujjain Empire and conquered the Scythian tribes c. 57 BC. Vikramaditya became one of the most celebrated heroes in Indian history – his name became a honorific title throughout India (analogous to Caesar, or Sikandar), and his victory over the Scythians marks the epoch of the Indian calendar. He heavily employed Sanskrit in administration (which had previously only been the language of academia), and Vaishnavism grew in importance.

The Ujjain empire dominated North-Western India until the invasion of the Tibetian Kushans c. 78 AD, who sponsored two pre-existing Scythian satraps of the Ujjain Empire: the Kshaharatas (led by Nahapana) and the Kardamakas (led by Rudradaman). Traditional legend holds that the Scythians were backed in their war against Ujjain by Shalivahana (possibly the same as Sivasvati), the emperor of the Deccan who had married Scythian princesses and had formed alliances with them. Following the fall of Ujjain, however, the Deccan Empire itself came into conflict with the Scythians: Gautamiputra Satakarni defeated the Kshaharatas, but his son Vashishtiputra Satakarni lost most of the reconquered territory to the Kardamakas.

The Kushans were the only pre-Islamic foreign dynasty to hold a lasting presence in inner India (i.e. Mathura and Ujjain), ruling as far as Ayodhya at their peak, before being defeated c. 200 AD by an alliance of Indian states including Ujjain, Mathura (Nagas of Padmavati), and the Yaudheyas of Punjab. Despite their foreign origin, the Kushans and their Scythian vassals were not necessarily barbarians in the same vein as earlier Scythian invaders. As feudatories of Ujjain, the Scythian tribes in India (as well as earlier Greek migrants) had assimilated into the kshatriya caste, using Sanskrit in their administration, paying homage to Indian philosophies and deities in their inscriptions and adopting Indian technologies.

They were particularly impressed by the toilet, which they held in ritual importance and called “the most meritorious gift” to be given in royal donations and political treaties.

Meanwhile, the more peaceful South had risen as the center of worldwide trade and commerce, as well as a host for Jewish and Christian refugees from the Roman Empire. The Deccan Empire facilitated the transmission of ideas between North and South, and traded extensively with the Romans as well as the East. The Deccan was a hub of metallurgy, alchemy and mechanical engineering, and Pratishthana was major a center of philosophy. In particular, the region gave birth to the Mahayana school of Buddhism, which was more open for debate and interaction with other Indian philosophies than was traditional Buddhism.

Kalinga also reached a period of prosperity, patronizing in particular Jain scholars; while Brahmin scholars seemed to have turned their eye away from mathematics in this period, instead focusing on things like legal theory, the baton was picked up by Jain mathematicians who made a wide array of contributions to the traditional subjects of Indian mathematics.

Classical Age: Second Golden Age (250 – 543)

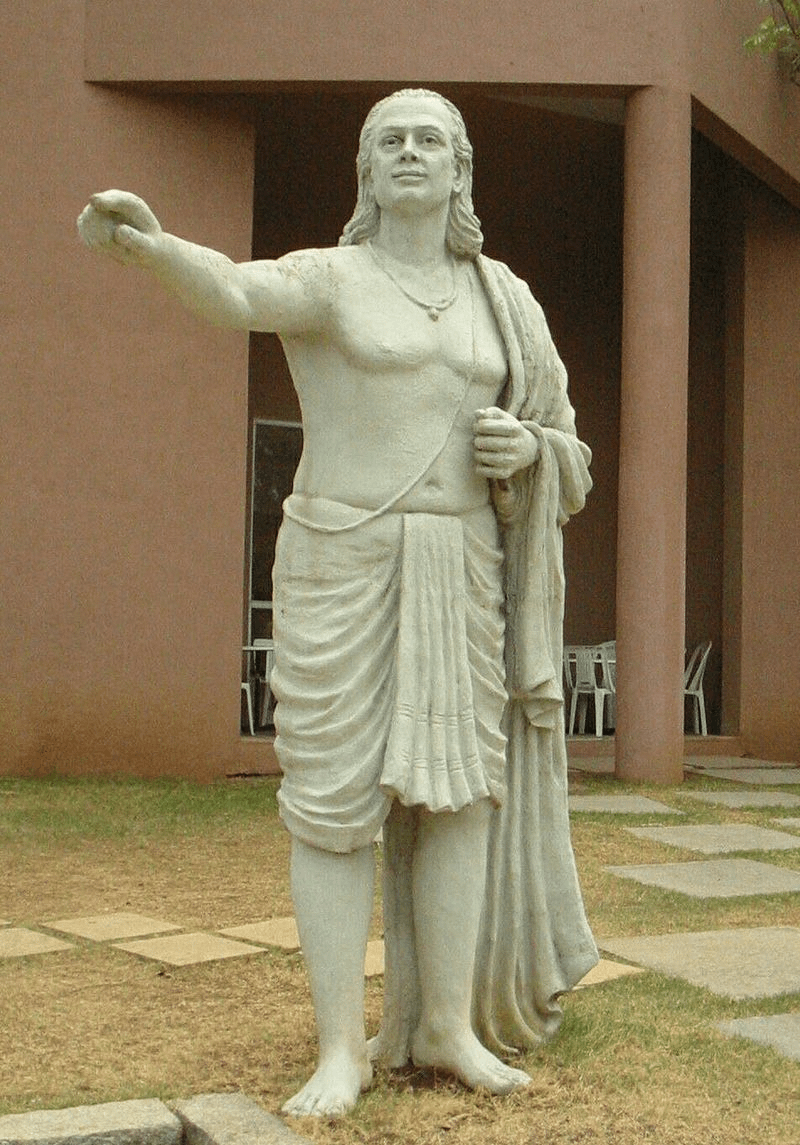

The Magadhan Empire re-rose to prominence under the Gupta dynasty. Like the Mauryas before them, the Guptas were probably also of non-Kshatriya (either Vaishya or Brahmin) birth and were foreign to Magadha (originating in Ayodhya or Mathura) – they patronized the Vishnu cult, and held the mythical eagle Garuda as their motif.

The Gupta period saw significant advances in mathematics, astronomy and metallurgy as well as the flourishing of literature and culture. Many of India’s greatest classical scientists (e.g. Aryabhata, Varahamira) date to this period, and the university of Nalanda was founded during the period. Much of earlier literature – including academic treatises and epics – were canonized in this period.

This period also saw the convergence of Vedic and Buddhist philosophies. The Mahayana school that had originated in the South became popular among Buddhist scholars in Gupta universities, and discussed topics of philosophy and logic without too much concern for ascetism. Vedic philosophy, which did not have a formal proselytic tradition to preach to the masses as such, allied itself with various local and rural cults (e.g. various rural cults were unified under the banner of Shaivism, several elite theistic movements were unified under the banner of Vaishnavism). Public Hindu temples became commonplace, tour guides were published and circulated for various cities and sites marketing them as pilgrimage locations. Carvaka was also apparently no longer considered part of the Vedic lore.

The history of the caste system also becomes worth mentioning here: the caste system was initially developed as a social theory by Yajnavalkya in the Middle Iron Age, and was strictly occupational (see e.g. the tale of Satyakama Jabala); by the end of the Late Iron Age, caste-segregated cities were a thing, and during the Invasions period legal theorists advocated for giving a legal basis for caste – even the school of Kautilya asked for heavy fines on Shudras pretending to be Brahmins, although they allowed the son of an upper-caste father by a lower-caste mother to take the caste of his father if he were “sufficiently manly”. By the Gupta era, earlier Indian hygiene norms had been codified into the more religious notion of “purity” and used as a religious basis for caste; thus intercaste marriages ceased.

A second wave of invasions – this time by the Huns – began c. 460 AD. While the Magadhan empire successfully repelled these attacks, the wars drained the state treasury and the Huns sacked several cities, destroying the ancient university of Taxila. The Huns were eventually expelled from India by an alliance of Indian states led by the Ujjain Empire under Yashodharman, who also annexed much of the territory held by the now-weakened Magadha.

Classical Age: Intermediary period (544 – 749)

This period begins with the end of the Gupta dynasty and ends with the beginning of the Tripartite struggle for Kannauj.

The main development of this period is the decline of Magadha as a region of relevance after 1000 years of political dominance over India. Indian science moves Westward and Southward, with mathematicians such as Brahmagupta and Bhaskara I hailing from Ujjain and the Deccan respectively.

Classical Age: Third Golden Age (750 – 1194)

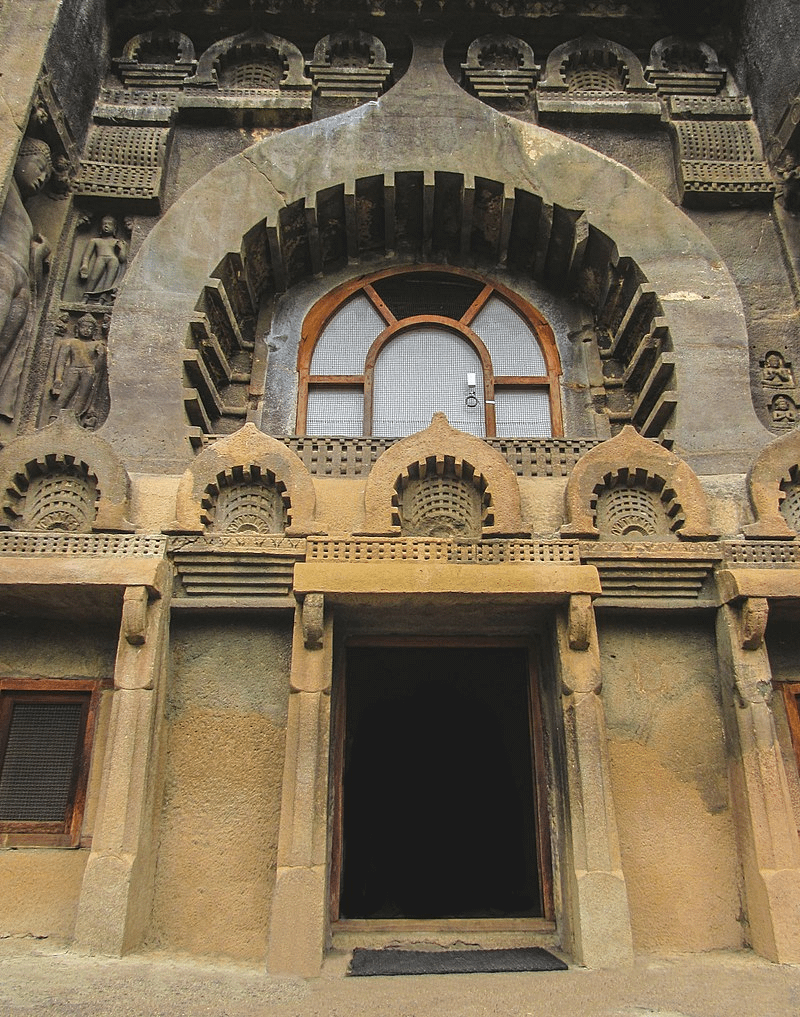

The Third Golden Age is the golden age of Southern India, beginning with the ascendancy of the Rashtrakutas to the Deccan Throne, which moves Southward from Pratishthana to Manyakheta, a city in North Karnataka metropolis. Brahmin and Jain mathematicians flourish in the Deccan Empire, and vast architectural projects are undertaken near Pratishthana.

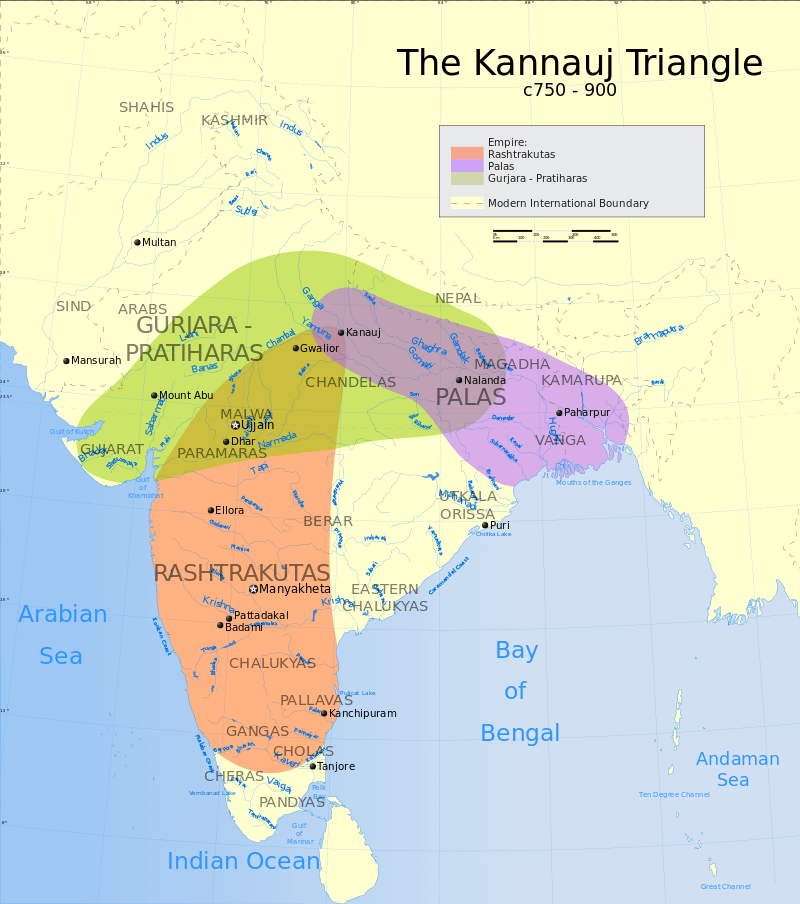

In the North-West, Arab invasions slowly expanded Islamic influence in the Pakistan region, but were held off by the Ujjain Empire under the Pratihara (“Gate-keeper”) dynasty. Astronomy continued to flourish in Ujjain even after the fall of the Pratiharas in the 11th century, with the famed scholar-king Bhoja reigning in this period. Meanwhile, the Magadhan Empire was no longer based in Magadha, with their capital now moved into the Anga region under the Pala dynasty. The period saw a 200-year long tripartite war (750–950) between the three empires for control over the Gangetic metropolis of Kannauj.

The Vedanta philosophy expanded in popularity among the elite, replacing both more rationalistic schools (such as Nyaya and Samkhya) as well as less rationalistic ones (such as Buddhism). While Shankara’s school of Non-Dualism is still not really theistic in a technical sense, Madhava’s Dualism is thoroughly theistic and religious.

In the Tamil country in the far South, the Chola empire overthrew the reigning Pallavas, bringing an end to six centuries of non-Tamil rule. The Cholas were a powerful imperial power, controlling much of South-East Asia at their peak. The Cholas’ contribution to naval engineering was extensive, and had a large influence on Arab and Chinese shipbuilding.

As a result of the historical prominence of Indian merchants (which had albeit declined during this period), Indian mathematics (as well as astronomy, medicine) had a large influence on the Muslim world (the famous developments of the Islamic Golden Age were largely based on Indian innovations) and later the West. The most important of these influences was on Fibonacci, who brought the sciences back into Europe and put an end to the European Dark Ages.

On the other hand, influences from the outside were greatly reduced, and India failed to adopt the various innovations of the Tang-Song Golden Age of China.

Dark Ages: Muslim period (1195 – 1669)

The Dark Ages of India begin with the invasions of the Turk Muhammad Ghori, whose slave Qutb al-Din Aibak established the Delhi empire. This was the first of the many Muslim invasions of India, several of which established new dynasties centered around the Delhi region, such as Timur’s Sayyid dynasty and Babur’s infamous Mughal dynasty. The Dark Ages reached different regions of India at different points in time – in the South, classical Indian civilization prospered until the Battle of Talikota in 1565.

Cities were razed; universities, libraries and temples were burned; high taxes and idiotic economic interventions were imposed. Non-Muslims were widely persecuted, and the total death toll of the Muslim invasions is widely cited as ~80 million. Slavery, widow-burning and child marriage spread, and India’s fraction of the world economy halved.

The sole exception to the widespread crappiness of the period was the rule of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (reign 1556-1605), who enacted several economic and social reforms, appointed Hindu ministers and partially Indianized court style. He grew disaffected with Islam, holding religious debates at the famously free Ibadat Khana and eventually left the religion mid-way into his reign for Din-i-Ilahi, a syncretic cult of his own creation. The Indian fraction of the world economy expanded during his reign for the first time in centuries, particularly fueled by the growth of the textile industry in Bengal. It is to the period of Akbar (and about two generations after him) that we owe the fancy wealthy picture of the Mughals, prior to which they lived in tents and ate rats.

As most men are fettered by bonds of tradition, and by imitating ways followed by their fathers… everyone continues, without investigating their arguments and reasons, to follow the religion in which he was born and educated, thus excluding himself from the possibility of ascertaining the truth, which is the noblest aim of the human intellect.

– Akbar, in a letter to King Phillip II of Spain.

Thus we see in this Prince [Akbar] the common fault of the atheist, who refuses to make reason subservient to faith, and accepting nothing as true which his feeble mind is unable to fathom, is content to submit to his own imperfect judgement matters transcending the highest limits of human understanding.

– Jesuit missionaries on Akbar.

Akbar’s reforms prompted several rebellions and attempted coups, and were gradually undone by his successors, particularly by his great-grandson Aurangazeb, who was pretty much worthless.

(I’m aware that many on this sub dislike Akbar for various brutalities he committed in his wars; I’m not really knowledgeable to comment on these, regardless I think it’s reasonable to speak well of someone’s positive accomplishments. For someone born to a barbarian dynasty of nomads, his achievements are no small feats.)

Dark Ages: Reconquest period (1670 – 1756)

The final leg of premodern Indian history was the reconquest of the country by Indic powers – most importantly Shivaji’s Maratha empire, but also Mysore and the Sikh dynasty.

The Marathas under Shivaji, who initially scored his victories through guerilla warfare and cunning, eventually received the backing of many financiers and landlords dissatisfied with Mughal rule. Shivaji was a remarkably enlightened ruler; he embraced Vedic rituals and governance policies, he was open to trade and adoption of foreign technologies, he regarded his conquests as a constructive enterprise rather than mere revenge against Muslim rule.

The Maratha Empire reduced the excessive bureaucratic overhead that had been introduced by Muslim rule, reducing taxes and abolishing religious persecution.