NiṣādaHermaphroditarchaṃśa (Mal'ta boy ka parivar)

Vikramaditya; reconstructing the interregnum of 57 BC – 78 AD

Myth: Vikramaditya never existed, he’s just a legendary ruler based on Chandragupta II; there is no epigraphy or coinage issued by him, and he is not mentioned in the dynastic histories (vamsanucharita) of the Puranas.

Overcorrection: Vikramaditya not only existed, but became a world-emperor, ruling over the Middle East, Central Asia, Eastern Europe and Western China.

The Maurya-Gupta interregnum (180 BC – 250 AD), in particular the period 57 BC – 78 AD, was a giant mess when it comes to the history of North-Western India.

South India under the Satavahanas and North India under the Shungas and successive Magadhan dynasties prospered in this period under relatively stable Vedic governance. In the North-West, however, the situation could only be described as political chaos.

There is already confusion about the political history in the period of Greco-Bactrian invasions before 57 BC1, and during the period of Scythian invasions, sovereignty was fuzzy and fluctuating, borders were non-constant or even ill-defined, and the chronology is highly uncertain. It would perhaps be most accurate to refer to the period as a complex multipartite war between the Greco-Bactrians, Scythians, Parthians, Yuezhi and local and imperial Indic states.

In the midst of all this chaos, there is one name that shines most brightly: Vikramaditya of Ujjain – who, as per traditional record, emerged victorious over the invaders and established a glorious golden age of prosperity and governance in accordance with Vedic laws. His victory over the Scythians c. 57 BC marks the epoch of the Vikrama Samvat, the traditional Hindu calendar – and his name was immortalized by history as a regal title, equivalent to “Caesar” in Europe or “Alexander” in Persia.

The purpose of this text is to reconstruct a precise history of the period between 57 BC – 78 AD based on the primary sources available to us.

If you’re unfamiliar with the historical context, read the background chapters first.

Table of contents

-

Historicity of Vikramaditya

-

Reconstructing the period 57 BC – 78 AD

-

Aftermath: 78 – 250

-

Background: start of the barbarian invasions

-

Background: 180 – 57 BC

Historicity of Vikramaditya

The most informative secondary source I found on this matter is Luniya (1972)2 (quick popular summary3), which is comprehensive. I will reproduce his arguments below.

Historians claim that the Vikrama Calendar (the most obvious evidence in favor of Vikramaditya’s historicity) doesn’t appear until the year 737, well after the end of the Gupta period.

However, this is only true in a very technical sense. The Yupa inscriptions4, made between the 3rd and 5th centuries, are all dated based on an era beginning in 57 BC called the Krta era:

-

The Nandsa sacrificial pillar, dated to Krta year 2825

-

The Badwa sacrificial pillar, dated to Krta year 2956

-

The Barnala sacrificial inscriptions, dated to Krta year 284 and 3357

-

The Vijaygarh inscriptions, dated to Krta year 428

-

The Mandsour inscription, dated to Krta year 461 [alongside later inscriptions]

-

The Gangadhara inscription, dated to Krta year 480

-

The Nagari inscription, dated to Krta year 481 [alongside earlier inscriptions]

Then between the 5th and 10th centuries, the same era appears under the name of the Malava era:

-

The Mandsour inscription of 461 refers to the era as both Krta and Malava8

-

The Mandsour inscription of Kumaragupta, dated in the era of the Malava Republic

-

The Mandsour inscription of Yashodharman, dated in the era of the Malava Republic year 589

-

The Kanaswa inscription of Sivagana, dated to Malava year 7959

-

The Gyaraspur inscription, dated to Malava year 93610

And finally inscriptions from the 9th century on use the term Vikrama era:

-

The Ahara inscription of Allata, dated to Vikrama year 810

-

The Dhaulpur inscription of Chanda-Mahasena, dated to Vikrama year 973

-

The Bijapur inscription of the Rashtrakuta Vidagdharaja, dated to Vikrama year 973

-

A Bodhagaya inscription, dated to Vikrama year 1005

-

The Ekalingaji inscription of Naravahan, dated to Vikrama year 1028

-

The Vasantagadh inscription of Purnapala, dated to Vikrama year 1099

This establishes a cultural continuity in the use of the era – It’s far harder to accept that people in 225 were ignorant of the events of 57 BC, than that people in 810 were. Also, since the earliest appearances of the Krta era predate Chandragupta II, the theory that Vikramaditya is entirely a character based on Chandragupta II is demonstrably false.

Luniya has an interesting theory for the change of terminology: he suggests that the earlier omission of the personal name from the name of the era is a result of the republican nature of the Malavas; Vikramaditya was the chief of a republic, rather than a king, and thus their victory would not be attributed to him alone. Once this republican origin was forgotten, Vikramaditya received individual veneration.

Of course, this is speculative, but it would also resolve the other argument against Vikramaditya’s historicity: his apparent omission from dynastic histories in the Puranas. Luniya points out that the Puranas11 do mention the Gardabhila dynasty, a house of the Malavas, which later Jain literature associates with Vikramaditya.

Historians claim that there is no numismatic evidence for Vikramaditya. This appears to just be blatantly false on multiple levels. First, early Indian coins (until Vasishthiputra Pulumavi, c. 100 AD) did not carry legends or kings’ portraits, but instead simple geometric designs. Second, hordes of unidentified coins have been found from the period, including at Ujjain. In particular, more than 6000 coins have been found at Malavanagara12 -- one group of such coins explicitly bears one of two Brahmi legends:

Malavanam Jayah

(The victory of the Malavas)

And:

Malava Ganasya Jayah

(The victory of the Malava Republic)

Some of these coins contain a king’s portrait, the others have a vase, lion, bull, fan-tail-peacock, etc. as the reverse design.

For completeness I will mention that there are also some bolder claims from more recent times13, claiming to have found coins with a portrait of Vikramaditya; these appear to me as unreliable at least in their reporting.

Even in the absence of such explicitly positive evidence, there would have been reason to believe the historicity of Vikramaditya; namely, the radical change in the culture of the Scythians between 57 BC and 78 AD, which is likely to be attributed to powerful influence from Ujjain. In particular, the Sanskrit epigraphy that the Indo-Scythians later became famous for has its roots in earlier Malava Sanskrit epigraphy (namely the Hathibada Ghosundi inscriptions14).

Thus all that needs to be ascertained is the precise level of power and territorial extent the Malavas had through this period.

Reconstructing the period 57 BC – 78 AD

(Again, if you are not familiar with the background of the Greco-Bactrian and other invasions of India starting 180 BC, I suggest reading the background sections first.)

We will first list the important primary-sourced facts based on which we will make our inferences:

-

The Scythian invader Maues had overstruck of the coins of the Indo-Greek Archebius in Taxila.

-

An Indo-Greek coin bearing the inscription “rajatirajasa moasa putrasa (ca) artemidorosa”, reading either as “Maues’s son Artemidoros” or “Maues and the son of Artemidoros”; in either case, Maues allied with at least some Indo-Greek houses.

-

The Parthian Vonones of Sakastan briefly occupied Taxila during Maues’s reign, as evidenced by his coinage.

-

Vonones’s successors Spalahores and Spalirisos were both Scythians, and did not occupy Taxila; thus various Parthian and Scythian houses were allied or even mixed in their invasion of India.

-

Indo-Greek Apollodotus II later overstruck Maues’s coins in Taxila, probably after Maues’s death.

-

The Indo-Scythian Azes ruled Taxila sometime after these early Parthians, and overstruck the Greek coins. His successor was Azilises.

-

The Apracharajas who ruled from Bajaur (a little North of Taxila) seemed to be much more Indian, although they are typically classified as Indo-Scythian. They were probably descended from the Vedic Ashvakas (based on their name and their region); their rulers’ names are very Indic; their language, script and philosophies appear to have been Indic. The names of some Queen consorts are more Iranian, however, and they feature some Greek deities on their coins, so they may have mixed with Scythians and Greeks. Their territory probably did not extend much beyond Taxila.

-

Zeionises ruled from West of Taxila, contemporary to some of the Apracharajas, and may have briefly occupied it. His successor was Kharahostes, who was apparently allied with the Apracharajas15 as suggested by the Silver Reliquary of Indravarman, so it is possible these were simply allied houses that ruled Taxila jointly in a republican fashion. The Mathura Lion Capital inscription refers to this house as Kamuia, which may be Kamboja (which would again suggest significant mixing between such tribes).

-

The Indo-Parthian Gondophares certainly occupied Taxila at some point, it was their capital; they’re often held to have ruled the entirety of territory from Sakala to Sindh, but these are probably fanciful accounts based on Philostratus’s unreliable Life of Apollonius Tyana.

-

Kharahostes’s son Mujatria and the Apraca ruler Sasan were again sovereign, and are known to be contemporary with the Kushan invader Kujula Kadphises (45—50 AD) based on hoard finds and overstrikes on Mujatria’s coins by Kujula’s successor Vima Takto.

-

But the Indo-Parthian Abdagases I (45—60 AD) also issued coins at Taxila16. So again, battlefield. Or vassals, but this seems unlikely.

-

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. 70—80 AD) attests a Scythian kingdom in Sindh with Minnagara as its capital, and mentions the circulation of coins with Greek legends in Bharuch17.

-

The Scythians Hagamasha and Hagana are known to have issued coins in Mathura at some point, and were called Kshatrapas. Rajuvula was referred to as a Mahakshatrapa. These two may have been predecessors of Rajuvula, his successors, or his contemporary vassals.

-

There are coins issued by an Indo-Greek ruler Strato II, many of which are found alongside Rajuvula’s at Sakala and Mathura1819, suggesting that (1) they are contemporaries and (2) that the Indo-Greek kingdom rose again at some point between 20 BC and 10 AD.

-

Sodasa was Rajuvula’s son, as per the Mathura lion capital. His inscriptions are only found in Mathura, so the Scythian territories in Sakala were probably lost again in this period.

-

No Scythian rulers are attested in Mathura from Sodasa c. 15 AD until Kharapallana and Vanaspara, vassals of Kanishka I c. 130.

-

For dating: the Taxila copper plate, suggesting a Maues era starting in 72 BC; the Bajaur relinquary inscription, suggesting an Azes era starting in 45 BC, and dating the Apracharaja Vijayamitra’s reign to 12 BC – 20 AD. The precise regnal years of the Apracharajas – Vijayamitra, Indravasu, Visnuvarma, Indravarman, Aspavarma, Sasan – overlap and are weird as everything else here is. Western records clarify Indo-Parthian rule to have began c. 19 AD. Rajuvula’s reign is pinned down to c. 10 AD by the Mathura lion capital that establishes his generational relationship to Kharahostes. Kujula Kadiphses is known to have existed c. 70 AD.

I will add some comments about the Scythian rulers of Mathura, aka “The Northern Satraps”.

I find the mainstream data of 60—50 BC for the Scythian conquest of Mathura to be highly improbable for several reasons: (1) that would mean stable and long reigns for Hagamasha and Hagana, quite rare in this chaotic period (2) Strato II’s coins at Mathura paint a picture of a Rajavula invading from the West, rather than his dynasty already having been established at Mathura. Thus I find it likely that Hagamasha and Hagana were either vassals of Rajavula, his successors, or minor Scythian houses that were involved in a multipartite struggle for Mathura (which succeeded upon Rajavula’s ascension) in a short period before him.

The other question is who these Northern Satraps were Satraps to. Perhaps they were satraps to the Scythians at Taxila as mainstream history holds (this seems unlikely, since Sodasa did not control Sakala and so this would mean being vassal to a territory he was not contiguous with) or to some other Indian state, but it seems more likely to me that they used the terms in a similar manner to the later Western Satraps: the reigning monarch was called a Mahakshatrapa, and his princes were called Kshatrapas.

Here’s the whole political history summarized. If anyone has the time to make an Ollie Bye-style visualization of this, be my guest.

+——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | ** | ** | S | **Mat | ** | **Bh | **U | | Year | Taxila** | akala** | hura** | Sindh** | aruch** | jjain** | +========+==========+=========+========+=========+=========+=========+ | 180 BC | Gandhara | Ayu | Mitra | Misc | Misc | Shunga | | | x | dhajivi | | Indic | Indic | | | | | | | | | | | | Greek | | | | | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 170 BC | Greek x | Ayu | Mitra | Greek | Misc | Malava | | | | dhajivi | | | Indic / | | | | Gandhara | | | | | | | | | | | | Greek | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 160 BC | Greek | Greek | Mitra | Greek | Misc | Malava | | | | | x | | Indic / | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Greek | | Greek | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 100 BC | Greek | Ayu | Mitra | Greek / | Greek / | Malava | | | | dhajivi | | | | | | | | | | Misc | Misc | | | | | | | Indic | Indic | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 70 BC | Scythian | Ayu | Mitra | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | x | dhajivi | | Indic / | Indic / | | | | | | | | | | | | Parthian | | | Greek | Greek | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 57 BC | Greek | Ayu | Mitra | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | | dhajivi | | Indic / | Indic / | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Greek | Greek | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 45 BC | Scythian | Ayu | Mitra | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | | dhajivi | | Indic | Indic | | | | | / | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | S | | | | | | | | cythian | | | | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 12 BC | Ap | Ayu | Mitra | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | racaraja | dhajivi | x | Indic | Indic | | | | + | x | | | | | | | | | Greek | | | | | | Kamboja | Greek | | | | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 0 | Ap | S | Sc | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | racaraja | cythian | ythian | Indic / | Indic / | | | | + | x | x | | | | | | | | | S | S | | | | Kamboja | Greek | Greek | cythian | cythian | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 10 | Ap | S | Sc | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | racaraja | cythian | ythian | Indic / | Indic / | | | | + | | | | | | | | | | | S | S | | | | Kamboja | | | cythian | cythian | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 19 | Parthian | Ayu | Sc | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | | dhajivi | ythian | Indic / | Indic / | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | S | S | | | | | | | cythian | cythian | | | | | | | / | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | P | | | | | | | | arthian | | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 50 | (Ap | Ayu | Misc | Misc | Misc | Malava | | | racaraja | dhajivi | Indic | Indic / | Indic / | | | | + | | | | | | | | | | | S | S | | | | Kamboja) | | | cythian | cythian | | | | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Parthian | | | | | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 78 | Kushan | Ayu | Misc | S | S | Malava | | | | dhajivi | Indic | cythian | cythian | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 130 | Kushan | Kushan | Kushan | S | S | Sc | | | | | | cythian | cythian | ythians | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Malava | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+ | 250 | Kushan | Ayu | Naga | Sa | Misc | Malava | | | | dhajivi | | ssanian | Indic | | +——–+———-+———+——–+———+———+———+

Key: / means “or”, + means “in alliance with”, x means “adversarial to”

Aftermath: 78 – 250

I will say a couple of things about the Scythian resurgence in the 1st century.

These Scythians were divided into two houses: the Kshaharatas and the Kardamakas. The Kshaharatas were Bhumaka and Nahapana; the Kardamakas included Chastana (crowned 78) and Rudradaman (crowned 130).

It is often said that the Kshaharatas ruled strictly before the Kardamakas, but there was probably some overlap – Nahapana was defeated by Gautamiputra Satakarni, while Rudradaman (who was Chastana’s grandson) fought Gautamiputra’s grandson Vashishtiputra Satakarni.

These Scythians grew very powerful on account of their alliances; they were at complete peace with the Kushans, and they gave some daughters in marriage to the Satavahanas. Well, a certain Satavahana emperor is known to have accidentally killed his wife during intercourse22, so it is no surprise that the latter alliance was a bit more unstable.

These Scythians were highly Sanskritized culturally, and were primarily affected by Vedic political philosophy (although they also donated to Buddhists) – their inscriptions contain descriptions of the Purushartha philosophy in pure Sanskrit, they issued land grants and kanyadanas to Brahmins, held and participated in Swayamvaras, employed Brahmin ministers, fought wild tribes and built infrastructure (especially cisterns, which they held to be sacred), spared defeated rulers, etc.

Rudradaman, who is the lord of the whole of Malwa, Gujarat, Marwar, Sindh, Sauvira (Multan), Kukura (East Rajasthan), Aparanta (Northern Konkan), Nishada (tribals) and other territories gained by his own valour, the cities, marts and rural parts of which are never troubled by robbers, snakes, wild beasts, diseases and the like, where all subjects are attached to him, and where through his might the goals of righteousness, wealth and pleasure are duly attained.

– Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman.

He who by the right raising of his hand [possibly the Chakravarti Royal Gesture] has caused the strong attachment of Dharma, who has attained wide fame by studying and recalling, by the knowledge and practice of grammar, music, logic, and other great sciences, who is proficient in the management of horses, elephants and chariots, the wielding of sword and shield, pugilistic combat, in acts of quickness and skill in opposing forces … who has been wreathed with many garlands at the swayamvaras of princesses.

– Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman.

Rudradaman, who obtained good report because he, in spite of having twice in fair fight completely defeated Satakarni, the lord of Dakshinapatha, on account of the nearness of their connection did not destroy him.

– Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman.

The meritorious gift of Ayama of the Vachhasagotra, prime minister of the King Mahakshatrapa the lord Nahapana.

– Junnar inscription of Nahapana, 26.

Success! By Ushabadata, the son of Dinaka and the son-in-law of the king, the Kshaharata, the Kshatrapa Nahapana, who gave three hundred thousand cows, who made gifts of gold and a tirtha on the river Banasa, who gave to the Devas and Brahmanas sixteen villages, who at the pure tirtha Prabhasa gave eight wives to the Brahmanas, and who also fed annually a hundred thousand Brahmanas- there has been given the village of Karajika for the support of the ascetics living in the caves at Valuraka without any distinction of sect or origin, for all who would keep the varsha.

– Karla Caves inscription of Nahapana.

Success! Ushavadata, son of Dinika, son-in-law of king Nahapana, the Kshaharata Kshatrapa, inspired by true religion, in the Trirasmi hills at Govardhana, has caused this cave to be made and these cisterns.

– Nashik Caves inscription of Nahapana, 10.10.

Of the queen of the illustrious Satakarni Vasishthiputra, descended from the race of Kardamaka kings, daughter of the Mahakshatrapa Rudradaman, of the confidential minister Sateraka, a water-cistern, the meritorious gift.

– Kanheri Caves inscription by Rudradaman’s daughter/Vashishtiputra Satakarni’s wife.

They were also instrumental in the popularization of Greek astronomy in India, with the famous Yavaneshvara having been housed at Rudradaman’s court.

Background: start of the barbarian invasions

Ashoka’s authoritarian rule caused a tripartite division of the Mauryan empire shortly after his death c. 232 BC – the South seceded, and the North split into two empires ruled from Pataliputra and Ujjain. The political stability that Chanakya had created disappeared, and seven different Mauryan kings ruled in the next 50 years, before the dynasty was overthrown in a coup by Pushyamitra Shunga in 180 BC. The Shunga empire, as well as the Satavahana empire in the Deccan, were not only Vedic in their governance, their rulers were Brahmins by caste. The political power that the Buddhists had gathered during Ashoka’s reign disappeared.

(There is a certain analogy between the Maurya-Gupta interregnum and the Trump administration in the modern U.S. Here, Vedic philosophy is analogous to conservatism, and Buddhism is analogous to the left. While Vedic ideas were executed very efficiently, it became more of a big-tent philosophy, compromising on ideological purity; furthermore, while Vedism nominally won the battle in terms of political power, Buddhism’s cultural foothold only expanded.)

There is significant evidence that many politically influential Indian Buddhists were complicit in the barbarian invasions; the Milinda Panha describes Buddhist monks traveling to Central Asia to advise Menander I, Pushyamitra Shunga is recorded to have executed several Buddhists in Sakala for treason, and the Jains blame themselves (the Jain monk Kalaka) for inviting the Scythians to invade India, probably an appropriation of a Buddhist act (considering that the Jains were themselves persecuted by Ashoka, and Kharavela, who repelled Menander I’s invasion, was a Jain). As many Buddhists had been appointed to positions of political power under Ashoka and the same state infrastructure continued to exist under the early Shungas, it seems reasonable that they were capable of betraying the Shungas in some critical way.

An alternate reading is that the Greeks fanned the civil war within the Maurya empire to facilitate their invasion – this reading is supported by some supposed verses from texts called the Parampara-pustaka and the Yavanarajya-Vrttanta23, but I was not able to find these original texts, and I am doubtful of their authenticity.

Background: 180 – 57 BC

Messy notions of sovereignty predate the Scythian invasion. The Greco-Bactrian invaders themselves were highly decentralized into several houses, etc. and their relationships with existing Indian rulers were complicated (the latter were not deposed, but were also not on friendly terms necessarily – thus the state can only be described as war).

Demetrius I was the first of these invaders, who made it only as far as Taxila c. 180 BC. Several rulers are described in his immediate succession, including Pantaleon, Agathocles, Antimachus I, Antimachus II, Apollodotus I (it is unclear what their relationship was).

Apollodotus I was the most significant of these successors, who expanded Southward to Sindh (where his coins are found). He may have also attempted an invasion of Bharuch (as per the Periplus), but he was probably repelled by the Satavahanas.

Taxila and other cities in Gandhara continued to mint coins in the traditional Indian standard alongside Indo-Greek coins24 – this could suggest the existence of private coinage, but I find it more likely that the Indo-Greek houses existed alongside local Indian dynasties, and that these houses were adversarial to each other (as the existence of competing coinage shows), rather than vassal or allied25.

Menander I’s invasion c. 160 BC was much more serious, and is discussed extensively in Indian literature, such as in the fawning Buddhist Milinda Panha, which states that he ruled from Sakala (Punjab); he also certainly brought Taxila under his direct sovereign control, as local Taxila coinage ceases in this period. Besides his possessions in the Punjab region, though, his other expeditions are more confusing.

It is known that Menander launched a Gangetic campaign, with his army reaching Pataliputra (some historians are skeptical of this invasion, but it seems like obvious historical fact to me, corroborated by multiple sources26) – however, this only amounted to a brief raid, and the famed Kalinga hero Kharavela repelled him back to Mathura at least.

In Mathura too, coins of local Indian rulers – bearing names amounting to the Deva, Dutta and Mitra dynasties – are found uninterrupted alongside Indo-Greek coins. However, Greek control over Mathura is also described in Indian sources (e.g. the Yavanarajya inscription and various Puranas, although interestingly the Milinda Panha makes no mention of this).

There are some oft-quoted verses from the Vayu Purana 99.362, 99.383, tertially attributed to a certain Morton Smith 1973:

Asui dve ca varsani bhoktaro Yavana mahim

Mathuram ca purim ramyam Yauna bhoksyanti sapta vai

I wasn’t able to find these words in the Vayu Purana27, and I suspect that it is a fabrication, even if the inference may be justified.

The figure, 82 years for the duration of Yavana rule which Cunningham cited (NC 1872 p. 185), as it is not a round number, might be a real tradition for some particular place; if so, that place must be Mathura, as the figure is far too small for anywhere else except Sindh or Saurashtra, which cannot come in question as because later Puranic history is confined to the United Provinces and Bihar (CHI p. 307). This would make the [Indo-Greeks’] loss of Mathura shortly after 100 BC.

(WW Tran, The Greeks in Bactria and India, p. 32428)

I was able to find:

Thereafter, the untruthful and unrighteous Yavanas of great fury and little grace will rule here spreading their religion, spending vast riches and giving vent to their lust.

Those kings will not be duly crowned. They will have all the defects of the Kali Yuga. They will commit evil actions.

During the remaining period of the Kali Yuga, the kings will enjoy the Earth, not even hesitating to kill women and children and to destroy one another.

They will be devoid of Dharma, Kama, Artha (righteousness, love, wealth). All the common people coming into close contact with them, too will follow the customs and habits of barbarians.

They will act contrary to accepted traditions. They will destroy their subjects. The kings will be greedy and devoted to mendacious behaviour.

When their turn is over, women will outnumber men in that age. People will become increasingly deficient in learning and strength. Their lifespans will shrink.

(Vayu Purana, translated by GV Tagare, Part 2, 37.382-289 / p. 820-821.)

It seems likely that Mathura and other densely populated regions may have become a battlefield between Indian rulers and the Greeks without enjoying a stable government – much like Taxila had been during Demetrius’s invasion – while the Punjab, including Taxila, had become a core Greek territory under Menander I. It is also not clear what the relationship between the Deva, Datta and Mitra dynasties was precisely: there are several other Mitra dynasties that appear throughout the Gangetic plain in Panchala, Kaushambi and Ayodhya – it is possible these may have been private merchants or the sort of plutocratic governments mentioned in the Arthashastra and the Ashtadhyayi.

This “Mathura as a battlefield” hypothesis is also supported by the extensive growth of fortifications in Mathura during this period; it’s also worth noting that the architecture and art of Mathura in this period was not influenced by Greek styles, so governance was likely predominantly Mitra, even if they may have had to pay tribute to the Greeks2930.

As the Indo-Greeks were rarely a single unified state themselves (except under some rulers like Demetrius and Menander), the kingdom fragmented upon Menander’s death c. 130 BC. These fragmented Indo-Greeks quickly diminished in importance, paying tribute to Scythian invaders (where special Greek coins are found31) and to the Shunga empire (where various Indo-Greeks donated several monuments, both of Vaishnava and Buddhist sects).

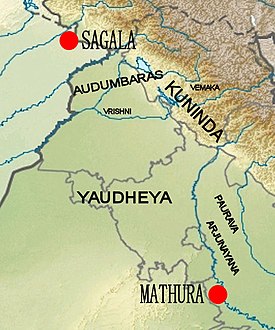

The Ayudhajivi Sanghas (war-like republics/corporations) that ruled East of the Ravi river rebelled c. 100 BC, ending Greek rule in Eastern Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Northern Rajasthan – notable among these corporations are the Yaudheyas, Arjunayanas, Audumbaras, Kunindas, Trigartas and Rajanyas. Their independence is known from the coins they minted with legends like32:

Arjunayanam Jayah

Yaudheya Ganasaya Jayah

Map of Ayudhajivi Sanghas33

They apparently remained allied against foreign invasions for several centuries to come. See also34. Also interesting to note: the Yaudheyas were apparently followers of Skanda/Kartikeya, the Arjunayanas were followers of Shiva, the Audambaras honored Sage Vishvamitra but also followed Skanda and Shiva, the Kunindas followed a Vaishnava-Buddhist syncretism like the Indo-Greeks.

The remaining Indo-Greek territories in the West (centered around Taxila) were reunified under Philoxenus c. 100 BC, and then fragmented again.

It was around this time that the conflict in Central Asia between the Yuezhi and the Scythians boiled over into India, with one of them or both apparently occupying Indo-Greek territories in Paropamisadae (Western Gandhara and Kamboja), and the Indo-Greek king Hermaeus c. 80 BC is shown in conflict with these nomads.

-

Erik Seldeslachts, The End of the Road for the Indo-Greeks, Iranica Antiqua 39 (2004): poj.peeters-leuven.be/secure/POJ/downloadpdf.php?ticket_id=600132d2b3c2e ↩

-

BN Luniya, Historicity of Vikramaditya, chapter in the English section of the Vikram Kirti Mandir Smarika (1972). Source: archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.538311/page/22/mode/2up ↩

-

Indian Herald (04/04/2018), pg 17. Source: issuu.com/indiaherald/docs/binder040418 ↩

-

See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y%C5%ABpa for a discussion ↩

-

Epigraphia Indica, Vol XXVI, pg 118-25 – see also Daniel Balogh, Inscriptions of the Aulikaras and Their Associates (2019), pg 20. Source: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RUDEDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA20 ↩

-

Epigraphia Indica, Vol XXIII, pg 43 – see also asijaipurcircle.nic.in/Badva.html, asijaipurcircle.nic.in/Yupa%20Pillars%20in%20Bichpuria%20temple,%20NAGAR.html ↩

-

See commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barnala_inscription.jpg, File:Barnala_inscription_2.jpg ↩

-

Fleet Gupta inscriptions, No. 33-34 ↩

-

Indian Antiquary, Vol XIX, pg 59 ↩

-

Archaeological Survey Report, Vol X, Plate II ↩

-

Vayu Purana XXXVII, 352-358; Brahmanda Purana XXIV, 171-178 ↩

-

Kailash Chand Jain, Malwa through the ages (1972), pg 6. Source: books.google.co.uk/books?id=_3O7q7cU7k0C&pg=PA6 ↩

-

See hindustantimes.com/bhopal/vikramaditya-steps-out-of-fables-into-history/story-myf7AvIkAVrySbYfSVuV2I.html and freepressjournal.in/ujjain/rare-coins-with-king-vikramadityaalt39s-image-found-at-ari ↩

-

Richard Salomon, An Inscribed Silver Buddhist Reliquary of the Time of King Kharaosta and Prince Indravarman, Journal of the American Oriental Society 116:3 (1996) p. 442. Source: doi.org/10.2307/605147 ↩

-

harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/175829?position=1 ↩

-

Periplus, Ch 47. ↩

-

Bratindra Nath Mukherjee, Mathura and Its Society: The Sacae-Pahlava Phase, Firma K.L.M. (1981) p. 9 ↩

-

Bibliography of Greek coin hoards, p. 194-195: numismatics.org/digitallibrary/ark:/53695/nnan63894/pdf ↩

-

Kama Sutra, Ch 7. ↩

-

Senarat Paranavitana, The Greeks and the Mauryas, p 78 (1971). Source: archive.org/details/thegreeksandthemauryassenartparanavitana1971_104_N/page/n47/mode/2up ↩

-

See Wikipedia for some images: [en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-Mauryan_coinage_of_Gandhara#Double-die_coins_(185BCE_onward)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-Mauryan_coinage_of_Gandhara#Double-die_coins(185_BCE_onward)) ↩

-

References: The Coins Of India, by CJ Brown, p. 13-20 (source); Ancient Indian Coinage, by Rekha Jain, p. 114. See also the Wikipedia article. ↩

-

Strabo 15.698, Gargi Samhita (Yuga Purana, ch. 5), Patanjali Mahabhasya 3.2.111, Hathigumpha inscription. ↩

-

Vayu Purana, translated by GV Tagare: archive.org/details/VayuPuranaG.V.TagarePart2 ↩

-

WW Tran, The Greeks in Bactria and India, p. 324: books.google.co.uk/books?id=-HeJS3nE9cAC&pg=PA324 ↩

-

Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE (2007), p. 10: books.google.co.uk/books?id=X7Cb8IkZVSMC&pg=PA10 ↩

-

MC Joshi, Mathura as an Ancient Settlement. ↩

-

Osmund Bopearachchi, Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné, p. 76. ↩

-

See LiveHistoryIndia for some images: livehistoryindia.com/story/history-of-india-2000-years/the-little-kingdoms-of-the-north-200-bce-200-ce/ ↩

-

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Indian_tribes_between_the_Indus_and_the_Ganges.jpg ↩

-

Vincent A Smith (MRAS, Indian Civil Service), Article 29 “The conquests of Samudragupta”: zenodo.org/record/2018768/files/article.pdf ↩