Early Vedic society and theological developments 🏗️

Table of Contents

- 1. Contents

- 2. Early Vedic outgroups

- 3. On the Dasyu and the “black skin” (Kṛṣṇā-tvac) in the Ṛgveda

- 4. Vrātyas were probably not outgroups

- 5. Speculative claims about Paṇis:

- 6. Note on demons:

- 7. Speculation on pre-Mauryan archaeological cultures

- 8. Theological developments c. 500 BC to classical

- 9. Further reading

- 10. Extra sources

The history of Hinduism — and the cultural history of India at large — is the history of assimilation.

The culture of the ancient Vedic elites occupies the dominant role in our understanding of Indian history due to their superiority in transmitting knowledge and their cosmopolitanism; however, throughout time there have been distinct cultures on this land, whose histories are shrouded in relative mystery, but which were eventually syncretized into the great alloy that is the Indian ethos of today.

This is a topic that gets a lot of unwanted attention from half-witted “sub-nationalist/separatist” (i.e. Periyarist, Ambedkarite, Khalistani, caste kangers) movements: these people’s historical knowledge is limited to idiotic interpretations of a few popular myths (”Vāmana-Bali/Mahiśāsura is about Aryans and Dravidians”, “Mohini/Ardhanārīśvara is about LGBT”). These crackpot delusions are anachronistic projections of simplistic racial narratives on the past, yet often obtain approval from mainstream writers due to the unholy leftist-subnat alliance. However, they are easily washed away with a rational and dispassionate analysis of the topic, which is what we will do here.

The history of Indian theology is however a rather vast topic, and this article only provides a broad overview. For those who want to read precise details, the undisputed living expert on this topic is mānasa-taraṃgiṇī (blog, history/hinduism/theology.org).

1. Contents

- Early Vedic outgroups

- List

- Vrātyas were probably not out-groups

- Speculative claims about Paṇis

- Speculative comments about Nāgas

- Note on demons

- Speculation on pre-Mauryan archaeological cultures

- Language distribution

- Substrate identification

- Mālaya tribe

- Fish-eater colonialism

- Material cultures

- The Rāmāyaṇa

- Theological developments c. 500 BC to classical

- The Bhagavata sect

- The Śaiva sect

- The Sūta literature

- Śramaṇa sects of note

- The Hindu Cosmology

- Bauddha, Jaina and Sangam theology

- Canonical and post-Canonical theology

2. Early Vedic outgroups

Early Vedic literature mentions a number of outgroups — noobs often incorrectly map this onto “Aryan” and “Dravidian” (categorizations which do not reflect how people in the Vedic era saw themselves), so it is important to more reasonably identify who these groups were.

List

- Dasyu — an Iranian people; presumably they were defeated and mass-enslaved in some war, leading to their ethnonym becoming synonymous for “servant”. See Encyclopedia Iranica’s entry on Dahyu, Dahae [1x.1] [1x.2], and this Stack Exchange answer [1x.3] refuting claims that they were of dark complexion.

- Mleccha — the earliest mention of this is from Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 3.2.1.23-24, which contains a sample of Mleccha speech (”he ’lavah! he ’lavah!”), and generally referred to an unintelligible language (due to the importance of precision of speech to the Ārya identity, it became a generic out-group identifier, like “barbarian”). (Etymology unclear; it may be related to “Meluḫḫa”, the Mesopotamian word for the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), but in this case I would speculate that the term really originated from an IVC term for the Baloch highlands, and was used for the IVC as a whole by the Mesopotamians due to its proximity to them)

- Paṇi — a wealthy mercantile people, derided for their wealth in the r̥g Veda but assimilated as Vaiśyas via the creation of the caste system in the Post-RV period (1000—800 BC). The term itself is cognate with Norse “Vanir”, the gods of commerce, similarly derided.

- Śiśnadeva — phallus-worshippers in the r̥g Veda, probably a precursor to Lingam-worship. Later commentaries interpret the term instead as “unchaste people”.

- Nāga — the term nāga itself is not mentioned in Vedic literature, (the Mahābhārata is first to use it), but the Vedic literature extensively speaks of a cult of sarpasatra, “The Serpent Sacrifice”, which may variously refer to a sacrifice by serpents, of serpents, or to serpents. A comprehensive source on this is [2] van den Hoek & Shrestha (1992), “The Sacrifice of Serpents: Exchange and Non-Exchange in the Sarpabali of Indrāyaṇī, Kathmandu”.

- Vrātya — fierce wandering ascetics; they were undoubtedly precursor to the Śaivite sect (they are mentioned in conjunction with deities such as Rudra and Paśupati) as well as to the ascetic (śramaṇa) influences on history/hinduism/philosophy.org. A comprehensive source on this is [3] ”Who were the Vrātyas?” by Sreenivas Rao.

- Niṣāda — a tribe that was “neither forest-dwelling nor settled” and were eventually assimilated into Vedic society, part of them Sanskritized into fully-enfranchised Āryas, part remained untouchable, and part expelled to frontier regions in the South and the East; see [4] and also later-cited [6x.1] which claims them to be related to the modern Nihali people.

3. On the Dasyu and the “black skin” (Kṛṣṇā-tvac) in the Ṛgveda

By now you surely know that the Dasyu were a proto-Iranian tribe. Interestingly even later Iranian languages use dāh for ``servant’’ [1x.2], so to argue it referred to “enslaved aborginals” you would have to believe in OIT.

DAHYU (OIr. dahyu-), attested in Avestan dax́iiu-, daŋ́hu- “country” (often with reference to the people inhabiting it; cf. AirWb., cot. 706; Hoffmann, pp. 599-600 n. 14; idem and Narten, pp. 54-55) and in Old Persian dahyu- “country, province” (pl. “nations”; Gershevitch, p. 160). The term is likely to be connected with Old Indian dásyu “enemy” (of the Aryans), which acquired the meaning of “demon, enemy of the gods” (Mayrhofer, Dictionary II, pp. 28-29). Because of the Indo-Iranian parallel, the word may be traced back to the root das-, from which a term denoting a large collectivity of men and women could have been derived. Such traces can be found in Iranian languages: for instance, in the ethnonym Dahae “men” (cf. Av. ethnic name [fem. adj.] dāhī, from dåŋ́ha-; AirWb., col. 744; Gk. Dáai, etc.), in Old Persian dahā “the Daha people” (Brandenstein and Mayrhofer, pp. 113-14), and in Khotanese daha “man, male” (Bailey, Dictionary, p. 155).

Already in 1912 the Old Persian ethnonym Daha- (Gk. Dáoi, Dáai; Lat. Dahae) had been connected by Sten Konow with Khotanese daha– “man, male,” an etymology that is all the more plausible as it is common throughout the world for nations to designate themselves with the words meaning “man” in their respective languages (for a few examples, see Bailey, 1958, pp. 109-10). The corresponding long-grade form \*dāha– is represented by New Persian dāh “servant,” Buddhist Sogdian dʾyh, Christian Sogdian dʾy “slave woman,” and apparently also Avestan \*Dāha-(or rather \*Dåŋha-), attested only as feminine Dāhī-, in Yašt 13.144, where it occurs, together with the Airiia-, Tūiriia-, Sairima- and Sāinu-, as the name of one of the tribes that followed the Zoroastrian religion. The fact that Old Persian Daha- and Avestan \*Dāha- seem to be related etymologically is not, however, necessarily proof that the two names referred to the same ethnic group; if the Daha- were indeed a Scythian tribe (see ii, below) it would be difficult to identify them with a group that is clearly excluded from the Airiia- (Aryans) in the Avesta. The ancient Indians also knew of a people called \*Dasa- (attested only in adjectival dāsa-), depicted in the Rigveda as enemies of the Ārya-. The same root is also apparent in Avestan dax́iiu-, Old Persian dahyu– (dahạyu-) “province” (i.e., “(mass of) people”; cf. Skt. dasyu– “(hostile) people, demons”), and perhaps also Avestan aži– dahāka– “manlike serpent” (cf. Schwartz, 123-24).

However some point at the term “kṛṣṇā tvac” (black skin) in RV 1.130.8, 9.41.1-2, 9.73.5 as evidence of racial animus against “pre-Āryan Indians”.

Peculiarly though, they never refer to any black-skinned people, just “the black skin” being defeated or driven away.

- RV 1.30.8: Indra overwhelmed the Kṛṣṇā tvac and punished the riteless in favour of Manu

- RV 9.41.1-2: The bright ones (drops of Soma) drive away the Kṛṣṇā tvac. We seize the dasyu.

- RV 9.73.5: [The Soma rays] blow away the dark skin, hated by Indra, from heaven and earth.

These would be quite weird things to say about a specific race of dark-skinned people you hate.

Note the use of different verbs: the dasyu are seized (as always), while the Kṛṣṇā tvac are driven away, blown away etc. So it is not like Kṛṣṇā tvac is an epithet of the dasyu.

Maria Schetelich in “The problem of the Dark Skin (Kṛṣṇā Tvac) in the Ṛgveda” [1x.4] has the most sensible explanation.

The Ṛgvedic people visualized the night as a black cloth or “skin” covering the sky.

Since the day-night cycle was seen as upheld by Vedic rites, riteless tribes would create an Endless Night: the Kṛṣṇā tvac.

Indeed, the “night as a black cloth covering the sky” metaphor is present elsewhere in the Ṛgveda, even though not specifically using the term Kṛṣṇā tvac which was reserved for the Endless Night.

Traditional commentaries from nearly three millennia later instead interpreted these verses as referring to the black skin of some rākṣasa being torn out, suggesting that this motif of the riteless creating an Endless Night had been forgotten.

4. Vrātyas were probably not outgroups

The more I read, the less the “Greater Magadha” theory makes sense. Neither Buddhism nor Jainism were born in Magadha proper but in the outskirts of Kosala and Vṛji respectively (which were important centers of Vedic scholarship).

Vrātya are attested well before Magadha and were probably roaming brotherhoods of (temporarily?) exiled sons from Vedic society (in fact apparently mostly Brāhmaṇas), and were responsible both for the settlement of Magadha and for the development of Śaivism.

The features attributed to “Greater Magadha” were either general features of Indian society (ascetism) or idiosyncrasies of Buddha (kṣatriya kanging).

5. Speculative claims about Paṇis:

The revival of many IVC traditions in the Second Urbanization (800 BC onward) is well-known, e.g.

- Units of mass: the classical Indian unit of mass is the ratti, the weight of a gunja seed ~0.113g. The Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa which mentions a unit called the Śatamāna which is 100 kr̥ṣṇalās, and the kr̥ṣṇalā is widely attested by later literature to be the same as a ratti; Gandharan coins from the Second Urbanization up to the time of Kautilya measure 100 rattis; the Kārṣāpaṇa itself is 32 rattis; the Arthaśāstra claims the purāṇa or “old” system of measurement had a standard of 32 rattis but proposes instead an 80-ratti standard called svarṇa which was use from Mauryan times onwards. Now what’s interesting is that the IVC weights belonged to a binary scale 1:2:4:8:16:32 where the smallest weight coincided with exactly 8 rattis, and the most commonly used weight was scale 4, i.e. 32 rattis, exactly what the Arthaśāstra calls the old system of measurement. Sources: [5x.1-2]

- Units of length: An ivory scale from Lothal has decimal divisions with each graduation of length 1.7mm, ten of these graduations equals the aṅgula according to the Arthaśāstra and such. Sources: [5x.3-5].

- Symbols on coinage: The Mohenjodaro class IV silver pieces and class D pieces are “remarkably similar” to later punch-marked coins [5x.6], and the symbols on IVC seals famously bear close resemblance to punch-marked coins [5x.7]. It is worth noting is that the IVC had “metals of fixed weight” for commerce, i.e. bullion/coins but without stamping [5x.8-13], and that the r̥g Veda itself mentions the term niṣka, which was at least later used to refer to coins explicitly, and even the Rig Veda use is suggestive (e.g. RV 4.37.4, 1.126.2) although the unambiguous use of the term to refer to currency only appears in Maṇdala 1 which was composed later (1000—800 BC). For a contrary perspective, see Cunningham [5x.14] who believes the weight of a kārṣāpaṇa coincided with that of the Phonecian shekel and thus derived from it.

- Misc: ivory dice, baked brick construction, bangles, generally similar craft industries, baths and stepwells, Yoga and meditative practices (if the so-called Paśupati seal is to be regarded as evidence for such). Sources: [5x.15].

Based on the especial prominence of activities related to trade and finance in these, and the fact that modern baniya (mercantile) castes have the greatest proportion of IVC ancestry, I am inclined to suggest that the Paṇi were the descendants of the IVC mercantile elite who preserved various IVC traditions and crafts into the Vedic period. Note also the similarity between the terms paṇi and paṇa and the derivation paṇi → vaṇij → baniya.

The comprehensive resource on this topic is [5] SC Malik (1968), Indian Civilization: the formative period, who postulates a similar theory. However, note that the book does make some mistakes, such as claiming the word pura has no Indo-European cognate (the Greek cognate is polis).

Speculative comments about Nāgas:

You will often see claims variously associating the Nāgas with tribes in Northeast India, Southeast Asia or Central-East India. Certainly, the term was later used to describe these tribes, but is quite absurd to claim that they all belonged to some widespread “Nāga culture”.

Instead, it seems to me that the Nāgas were a symbol of Hindu assimilation: a label assigned to any people who were initially foreign and hostile to the Āryas but eventually yielding to our ways. Of course, the motif would have been based on a real serpent-worshipping culture in the time of the Kuru kingdom (1000—900 BC), who were initially hostile to the Kurus but eventually made peace with them and assimilated culturally, as attested in the Mahābhārata in the story of Janamejaya and Takṣaka.

(Note that I am willing to accept the Mahābhārata for information on the Vedic period despite its varied period of composition ~1000 BC—400, because e.g. the sarpasatra is independently attested by Vedic literature without appearing to have been copied.)

6. Note on demons:

Sub-nat circles suffer from the Euhemeristic tendency of believing every mythic or legendary race of “demons” must be based on some race of people (invariably their own), e.g. Asura, Daitya, Dānava, Rākṣasa, Yakṣa. None of these are of Euhemeristic origin: Asura was a generic honorific for a powerful being like “Lord” and grew a negative connotation due to the popularity of David-vs-Goliath-style storytelling; this was not due to some conflict against the Zoroastrians, who simply retained the positive meaning of Asura (however, the Zoroastrian rejection of the Devas as demons was due to their dissent from the prevailing Vedic or para-Vedic culture in their early homeland in Afghanistan). The term Rākṣasa first appears in the epics, and based on its etymology (”protector”) could have either have been motivated by wild tribes protecting forests from the light of civilization or by guards of castles and treasures in heroic mythology. Alternatively they could be based on the Rakṣas people of Baluchistan mentioned by Pāṇini 5.3.117 (see VS Agarwala). Dānava frequently occurs in the r̥g Veda; both only appear in the Purāṇas; Daitya appears in classical texts such as the Manusmr̥iti only as celestial beings without any further negative connotation, both are purely mythical beings from their very conception. Yakṣa is a minor nature spirit in the r̥g Veda itself, a similar class of beings as the Gandharva, etc.

7. Speculation on pre-Mauryan archaeological cultures

All the aforementioned groups mentioned lived in the same geographic region as the Vedic people, i.e. Udīchya+Brahmāvarta+Madhyadeśa (Punjab+Haryana+UP) — except the Vrātyas who in the latter Vedic period settled the Magadha region (see source [3]), and perhaps the Mlecchas who I might have been of Sindh or the Baloch highlands. What, then, were the religions and cultures in the rest of the Loka, pre-Maurya?

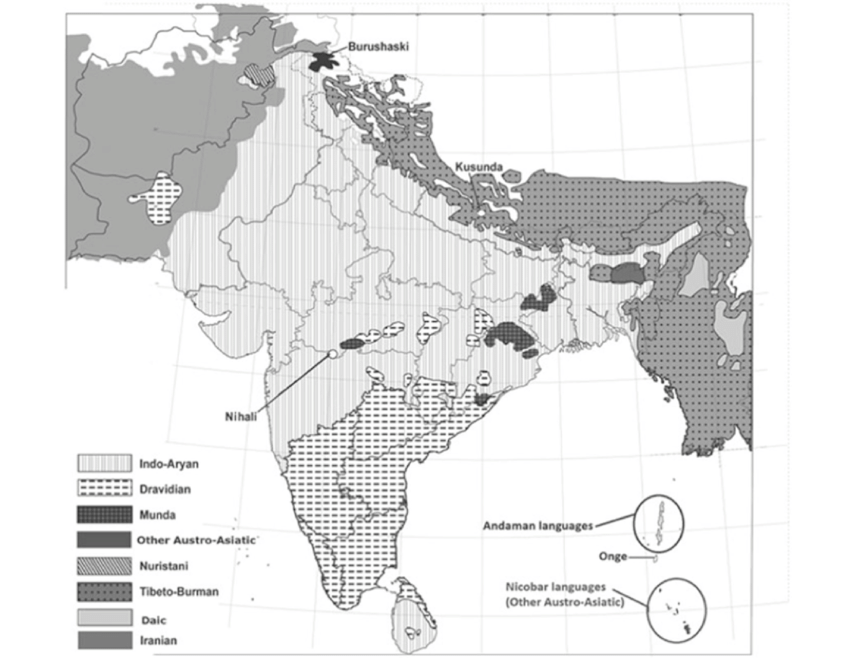

Language distribution: One piece of information is the current distribution of languages, which suggests a peninsular distribution of the Dravidian languages, Eastern distribution of Munda (Austro-asiatic), and the language isolates of Nihali, Burushaki, Kusunda and the remnants in Vedda, which may at one point have had a wider distribution.

Image: arxiv.org/pdf/2203.12524.pdf

Substrate identification: However, it is quite difficult to imagine that e.g. Dravidian could have had such a wide geographical distribution in neolithic/chalcolithic times, and this also doesn’t answer any question about the “pre-Aryan” languages in the North, or the language of the IVC. Certainly if we are willing to entertain that Nihali could have once had a wider distribution, then so could any language completely lost to us today. To have any shot at answering these questions, one must study substrates in extant languages: words in the language not attested in any cognate language, and which share some structure. Hypothesized substrates in Vedic Sanskrit:

- “para-Munda” substrate of Witzel [6x.1], characterized by words prefixed by k- such as even kumāra, names of plants and animals, names of many major rivers including the Gaṅgā, names of early chieftains in Punjab, names associated with the Kīkaṭa and Khāṇḍava, names of Eastern provinces ending in -ṅga (Aṅga, Vaṅga, Kaliṅga, Teliṅga)

- “language X” of Masica’s [6x.2], consisting of names of plants in the Gangetic plains

- “Indo-Iranian substrate” of Lubotsky’s [6x.3], consisting of words related to construction, camel (ustra) and even significant religious words like indra, atharva, gandharva.

- Dravidian substrate, discussed by Zvelebil [6x.4]; according to Witzel only appears in the middle RV period, and Dravidian was spoken in Sindh and Baluchistan

- “Meluhhan substrate”, which according to Witzel was spoken in IVC Sindh before the migration of Dravidians (from Baluchistan according to him, but I think could also be from the South)

- Tibeto-Burman substrate, according to Witzel, existed in the Kosala region.

Also worthy of note is the “Inner-Outer hypothesis” of e.g. Zoller [6x.5] (see also the comments by mānasataraṃgiṇī therein) which postulates two waves of Aryan migrations into India, one with more archaic Indo-Iranic features, preserved in the North-West, and another a standard Indo-Aryan one.

See also [6x.6] mānasataraṁginī’s comments on all this.

Mālaya tribe: The talk of a “para-Munda” language in Punjab may strike one as odd given its generally presumed Eastern provenance (indeed, Munda resurfaces in the names of Eastern provinces). However, a major Austro-asiatic presence has been noted by several authors including:

[7.1] PC Bagchi (1929), “Pre-Aryan And Pre-Dravidian in India”

[7.2] RC Majumdar (1937), Ancient Indian colonies in the Far East: Vol II (Suvarnadvipa), Part I (Political History). pgs 19-24. (my comments thereon)

[7.3] Joseph Minattur (1966), “Malaya: What’s in a name?”

E.g. Majumdar suggests that the various Mālayas:

- the Mālava tribe of Punjab that migrated to Ujjain or vice versa (attested as Mālaya in some coins, this is a standard sound change), and the related name “Malwa” for the Ujjain region

- the Dravidian term mala for mountain, preserved in the name “Mālaya” in Sanskrit literature for the Southern part of the Western ghats, and in the names Malayāḷam and Malabar for Kerala

- Malayaketu of the Mudra-Rākṣasa (interestingly the son of Parvataka, thus associated with mountains), Malayāvati the wife of the Kuntala king Śātakarṇi Sātavāhana in the Kāmasūtra

- Various Southeast Asian Malayas: Malaysia (Malayu, Malacca), Malayu in Sumatra, Māla or Mālava for Laos, Molucca islands in Eastern Indonesia

- Maldives (Māladvipa), Madagascar (whose people are known as Malagasy)

- (Majumdar doesn’t claim this) Perhaps even Meluḫḫa?

Are related, and that the tribe is of Austro-asiatic, i.e. “Para-Munda” origin.

Fish-eater colonialism: However incredible this claim of a great lost civilization spanning the seas in the LBA/EIA may seem, there is a third context wherein it has independently arisen, namely the early trade between the Indian West coast (both IVC Gujarat and the Konkan, Karnataka) and Sub-Saharan Africa [8x.1] [8x.2] and the mastery over the monsoon winds:

Material cultures: Perhaps we can get some hints from looking at archaeology? Here is a list of material cultures from North India known to archaeologists:

Table S1 of [9x.1]

In the Deccan you have the famous megalithic culture (dolmens and such) and ashmounds, which I cannot even find reliable dating for, and in the Tamil country you have sites at Keezhadi, Adichanallur, Anuradhapura etc. But this is all really disappointingly unexplored and doesn’t help us, though it is notable that the only clear examples we have of material cultures ~1300—800BC outside the Vedic realm are those of Madhya Pradesh, something also attested in e.g. the famous Bhimbetka caves. Indeed, even in the literature one observes the culture of the Pulindas is mentioned somewhat distinctly, e.g. [9x.2].

The Rāmāyaṇa

The Rāmāyaṇa appears to be based on a combination of real events of importance from the 8th or 7th centuries BC as well as an account of information from the earliest Ārya explorations of the peninsula (similar in mystique to e.g. the accounts of Indica by Herodotus or Ctesias). If you accept this general view, then the ambiguous names in the Rāmāyaṇa can be seen as a sample of words or names in the peninsula in those times: Hanumān, Vālī, Rāvaṇa, , Jaṭāyu, Sampāti, Kiṣkindhā, Rumā, Khara (note the name of later Kaliṅga king Kharavela), Mālyavān & related Māli, Mārīca, Śabarī (perhaps from the river Śabarī, a tributary to the Godāvarī), Tāṭakā (the yakṣa).

I think that in cases where a place is said to be named after a character, it is likely to be the reverse. E.g. according to [10x.1], the Śabarī river is named after the “Śabara”, a Telugu people; or the tale of Takṣaka in the Mahābhārata indicating a Nāga culture in Gandhāra before the dominance of the Kurus, or the tale of Mahiṣāsura for Mysore, of Vātāpi, of Śūrpaṇakhā based on the city of Śūrparaka. Their true etymology may lie in some (lost?) peninsular language.

(There have been some claims that the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa actually does not refer to an expedition to the South, that Laṅka is actually in Amarakaṇṭaka in Madhya Pradesh and that its identification with Siṃhala comes from the period of the Cōḻa imperialism in the island. This is definitively false: Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa 4.41 identifies the location of Laṅkā as being in the South, past the Pāṇdya country, opposite the ocean from the Mahendra mountains (Eastern Ghats): this can only be Sri Lanka. Besides, the Rāmāyaṇa is quite explicit in its geography, describing an overall Southern voyage, e.g. Pañcavaṭī forest, the site of Sītā’s abduction, is on the Godāvari river (Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa 3.64) and probably identifiable as Nashik. In the 4th century, the Laṇkāvatāra Sūtra, a Bauddha text, was composed in Siṃhala itself.)

8. Theological developments c. 500 BC to classical

The culmination of the theology of the previous period is the Br̥haddevatā, c. 500 BC. Subsequently many theological cults developed, some absorbing non-Vedic elements from the Vrātyas, Nāgas etc. some canonizing the songs of bards (the Sūta caste), and some independent developments.

8.1. Vaiṣṇava sources

- Vṛṣṇi heroes (c. 400 BC)

- Bhāgavata sect, probably the same as the Vṛṣṇi heroes

- Vedic Viṣṇu (<1200 BC)

- Nārāyaṇa, already associated with Viṣṇu in the Nārāyaṇa Suktam c. 700 BC but the Nara-Nārāyaṇa dichotomy has a proto-Dvaita feel to it

- Kṛṣṇa Devakīputra the student of Ghora Aṅgirasa, who promoted the Puruṣa Yajña and a proto-Gītā philosophy as per Chandogya Upaniṣad c. 700 BC

8.2. Śaiva sources

8.3. The Sūta literature

8.4. New cults

https://www.buddhisma2z.com/content.php?id=366

Some of the sects mentioned in the Tipiṭaka include the Ājīvaka (Those of the Pure Life), the Muṇḍaka Sāvaka (the Shaven Disciples), the Jaṭila (the Matted-hair Ones), Paribbājaka (the Wanderers), the Māgaṇḍka, the Tedaṇḍika (Those of the Tripod), the Aviruddhaka (the Free Ones), the Gotamaka (Gotama’s Followers), the Devadhammika (the Godly Ones), and the disciples of the mysterious Dārupāttika (He of the Wooden Bowl, A.III,276; D.I,157). These and other samaṇa sects were also collectively known as ‘ford-makers’ (titthiya) because they claimed to be able to show the way to ‘cross over’ from this world to the next. Later, Buddhists used this term for any non-Buddhist samaṇas. The two dominant samaṇa sects of the time, and the only ones to survive to the present, were Jainism whose followers were known as Nigaṇṭhas (The Bondless Ones) and Buddhism. The Buddha was often referred to as ‘the samaṇa Gotama’(D.I,4).

There was a great deal of religious switching at the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Buddha himself had been the disciple of two different teachers, Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, during his six-year search for truth (M.I,164-5). Early in his career three famous brothers, the Kassapas, who were the leaders of a band of Jaṭilas, became his disciples bringing all their followers with them (Vin.I,24-5). It was this incident more than any other that drew widespread attention to the Buddha so soon after he started teaching. Nanda Vacca, one of the supposed ‘three liberated ones’ of the Ājīvaka sect also converted to Buddhism (M.I,524). The two men who later became Buddha’s senior disciples, Sāriputta and Moggallāna, had both been Ājīvakas before becoming Buddhists. Occasionally, those who had been the Buddha’s disciples joined other sects, Sunakkhatta being an example of this (D.III,2). See Jainism and Subhadda.

https://twitter.com/Param_Chaitanya/status/1705414333851992112

Tripitakas very well known who Krishna and Balarama are

Cullaniddesa of Khuddakanikaya mentions the worship of different deities along with Krishna & Balarama, this description contradicts with Ghata-jataka

It also mentions the worship of Jaina deities Manibhadra, Purnabhadra

Here is the transcription, transliteration, and English translation.

### 1. OCR Transcription (Devanagari)

The text begins mid-sentence at the top, but the main paragraph is as follows:

खत्तिया ब्राह्मणा देवतानन्ति । खत्तियाति ये केचि खत्तियजातिका । ब्राह्मणाति ये केचि भोवादिका । देवतानन्ति आजीवकसावकानं आजीवका देवता, निगण्ठसावकानं निगण्ठा देवता, जटिलसावकानं जटिला देवता, परिब्बा जकसावकानं परिब्बा जका देवता, अविरुद्धकसावकानं अविरुद्धका देवता, हत्थिवतिकानं हत्थी देवता, अस्सवतिकानं अस्सा देवता, गोवतिकानं गावो देवता, कुक्कुरवतिकानं कुक्कुरा देवता, काकवतिकानं काका देवता, वासुदेववतिकानं वासुदेवो देवता, बलदेववतिकानं बलदेवो देवता,

पुण्णभद्दवतिकानं पुण्णभद्दो देवता, मणिभद्दवतिकानं मणिभद्दो देवता, अग्गिवतिकानं अग्गि देवता, नागवतिकानं नागा देवता, सुपण्णवतिकानं सुपण्णा देवता, यक्खवतिकानं यक्खा देवता, असुरवतिकानं असुरा देवता, गन्धब्बवतिकानं गन्धब्बा देवता, महाराजवतिकानं महाराजानो देवता, चन्दवतिकानं चन्दो देवता, सुरियवतिकानं सुरियो देवता, इन्दवतिकानं इन्दो देवता, ब्रह्मवतिकानं ब्रह्मा देवता, देववतिकानं देवो देवता, दिसावतिकानं दिसा देवता, ये येसं दक्खिणेय्या ते तेसं देवताति – खत्तियब्राह्मणा देवतानं ।

—

### 2. Transliteration (Roman Script)

Khattiyā brāhmaṇā devatānanti. Khattiyāti ye keci khattiyajātikā. Brāhmaṇāti ye keci bhovādikā. Devatānanti ājīvakasāvakānaṃ ājīvakā devatā, nigaṇṭhasāvakānaṃ nigaṇṭhā devatā, jaṭilasāvakānaṃ jaṭilā devatā, paribbājakasāvakānaṃ paribbājakā devatā, aviruddhakasāvakānaṃ aviruddhakā devatā, hatthivatikānaṃ hatthī devatā, assavatikānaṃ assā devatā, govatikānaṃ gāvo devatā, kukkuravatikānaṃ kukkurā devatā, kākavatikānaṃ kākā devatā, *vāsudevavatikānaṃ vāsudevo devatā, baladevavatikānaṃ baladevo devatā, puṇṇabhaddavatikānaṃ puṇṇabhaddo devatā, maṇibhaddavatikānaṃ maṇibhaddo devatā, aggivatikānaṃ aggi devatā, nāgavatikānaṃ nāgā devatā, supaṇṇavatikānaṃ supaṇṇā devatā, yakkhavatikānaṃ yakkhā devatā, asuravatikānaṃ asurā devatā, gandhabbavatikānaṃ gandhabbā devatā, mahārājavatikānaṃ mahārājāno devatā, candavatikānaṃ cando devatā, suriyavatikānaṃ suriyo devatā, indavatikānaṃ indo devatā, brahmavatikānaṃ brahmā devatā, devavatikānaṃ devo devatā, disavatikānaṃ disā devatā, ye yesaṃ dakkhiṇeyyā te tesaṃ devatāti – khattiyabrāhmaṇā devatānaṃ.*

—

### 3. Translation

The text defines who constitutes a “deity” for various groups of people, essentially stating that whatever object or being a person takes a vow to worship, that becomes their deity.

“Regarding ‘Kshatriyas and Brahmins are deities’:”

- “Kshatriyas”: Means anyone of the warrior/noble caste.

- “Brahmins”: Means anyone who uses the address “Bho” (referring to the priestly caste).

“Regarding ‘Deities’:” (The text now lists specific groups and their corresponding gods):

- For the disciples of the Ajivakas, the Ajivakas are the deity.

- For the disciples of the Niganthas (Jains), the Niganthas are the deity.

- For the disciples of the Jatilas (matted-hair ascetics), the Jatilas are the deity.

- For the disciples of the Paribbajakas (wanderers), the Paribbajakas are the deity.

- For the disciples of the Aviruddhakas, the Aviruddhakas are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Elephant (hatthi), the Elephant is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Horse (assa), the Horse is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Cow (go), the Cow is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Dog (kukkura), the Dog is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Crow (kaka), the Crow is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Vāsudeva (Krishna), Vāsudeva is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Baladeva (Balarama), Baladeva is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Puṇṇabhadda, Puṇṇabhadda is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Maṇibhadda, Maṇibhadda is the deity. (Note: Punnabhadda and Manibhadda were Yaksha generals worshipped in ancient India).

- For those who have a vow to Fire (aggi), Fire is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Nagas (serpents), the Nagas are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Supannas (Garudas/mythical birds), the Supannas are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Yakkhas, the Yakkhas are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Asuras, the Asuras are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Gandhabbas (celestial musicians), the Gandhabbas are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Great Kings (Four Heavenly Kings), the Great Kings are the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Moon (canda), the Moon is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Sun (suriya), the Sun is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Indra, Indra is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to Brahma, Brahma is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to a Deva (general god), the Deva is the deity.

- For those who have a vow to the Directions (disa), the Direction is the deity.

8.5. The Hindu Cosmology

seven continents, origin stories, yugas, manu, saptarsi, kasyapa, heaven vs reincarnation

- Bauddha, Jaina and Sangam theology

- Canonical and post-canonical (Tantra, Bhakti, Purana) theology

9. Further reading

Sources central to this topic, that you should follow as further reading

[3] ”Who were the Vrātyas?” by Sreenivas Rao

[5] SC Malik (1968), Indian Civilization: the formative period

[7.1] PC Bagchi (1929), “Pre-Aryan And Pre-Dravidian in India”

[7.2] RC Majumdar (1937), Ancient Indian colonies in the Far East: Vol II (Suvarnadvipa), Part I (Political History). pgs 19-24. (my comments thereon)

10. Extra sources

Sources that aren’t important enough to be fully described inline; i.e. basically any source that is relied on but isn’t a “comprehensive source on this sub-topic that you should read”.

[1x.1] Dahyu (Encyclopedia Iranica)

[1x.2] Dahae (Encyclopedia Iranica)

[1x.3] this Stack Exchange answer

[5x.1] BN Mukherjee (2012), “Money and social changes in India (up to AD 1200)”

[5x.2] Allchin (1964), An inscribed weight from Mathura.

[5x.3] Sergent, Bernard (1997). Genèse de l’Inde (in French), p. 113.

[5x.4] S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 39–40

[5x.5] Michael Danino (2018), The Meteorology behind Harappan Town-Planning – II.

[5x.8] Reddy, Deme Raja (2014). “The Emergence and Spread of Coins in Ancient India”, p 53.

[5x.9] Goyal, S. (2009). A history of the emergence of the Indian coinage. In Studies in Indian Coinage (special centenary volume), The Numismatic Society of India (pp. 58–59). Varanasi: BHU.

[5x.11] Bajpai, K. D. (October 2004). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications

[5x.12] Gupta, Paresh Chandra Das (1962). Excavations at Pandu Rajar Dhibi. p. 33.

[5x.15] Jim G Shaffer (1993), Reurbanization: The Eastern Punjab and Beyond

[6x.2] Masica, Colin (1979). “Aryan and non-Aryan elements in North Indian agriculture”.

[6x.3] Lubotsky, A. (2001). “The Indo-Iranian Substratum”

[6x.4] Zvelebil, Kamil (1990). Dravidian Linguistics: An Introduction

[6x.5] Zoller, Claus Peter (2016). “Outer and Inner Indo-Aryan, and northern India as an ancient linguistic area” (mānasataraṃgiṇī’s comments thereon)

[6x.6] mānasataraṁginī, “The substrate in Old Indo-Aryan”

[8x.1] Purushottam Singh (1996), “The origin and dispersal of millet cultivation in India”

[8x.2] Dorian Fuller (2003), “African crops in pre-historic South Asia: a critical review”

[9x.1] Khan & Lemmen (2013), “Bricks and urbanism in the Indus Valley rise and decline”

[10x.1] K. Lakshmi Ranjanam, “Andhra Culture, A Synthesis” in Triveni Journal, April 1952